As a young man in the nineteen-eighties, Tucker Swanson McNear Carlson set out to claim his stake in the establishment. His access to money and influence started at home. His stepmother, Patricia, was an heir to the Swanson frozen-food fortune. His father, Dick, was a California TV anchor who became a Washington fixture after a stint in the Reagan Administration. For fortunate clans like the Carlsons, it was “A Wonderful Time,” to borrow the title of a volume of contemporaneous portraits of “the life of America’s elite,” which included “the Cabots sailing off Boston’s North Shore, and Barry Goldwater on the range in Arizona.”

As a teen-ager, Carlson attended St. George’s School, beside the ocean in Rhode Island, one of sixteen American prep schools that the sociologist E. Digby Baltzell described as “differentiating the upper classes from the rest of the population.” Carlson dated (and later married) the headmaster’s daughter. His college applications were rejected, but the headmaster exerted influence at his own alma mater, Trinity College, and Carlson was admitted. He did not excel there; he went on to earn what he described as a “string of Ds.” After college, he applied to the C.I.A., and when he was rejected there, too, his father offered some rueful advice: “You should consider journalism. They’ll take anybody.” Soon, Carlson was writing for the Policy Review, a periodical published by the Heritage Foundation, followed by The Weekly Standard, Esquire, and New York, while also becoming the youngest anchor on CNN.

But, in 2005, Carlson’s CNN show was cancelled, and, after a period of wandering—including a failed program on MSNBC, a cha-cha on “Dancing with the Stars,” and an effort to build a right-wing answer to the Times—he found success at Fox News. There, he developed a dark new mantra. “American decline is the story of an incompetent ruling class,” he told his audience, in 2020. “They squandered all of it in exchange for short-term profits, bigger vacation homes, cheaper household help.” It was an audacious message from a man with homes in Maine and Florida, a reported income of ten million dollars a year, and Washington roots so deep that the Mayflower Hotel honored his standing order for a bespoke, off-menu salad. (Iceberg, heavy on the bacon.) But Carlson framed his advantages as proof of credibility; he told an interviewer, “I’ve always lived around people who are wielding authority, around the ruling class.” His origins helped give fringe ideas—such as the conspiracy theory that George Soros is trying to “replace” Americans with migrants—the ring of inside truth. His eventual firing from Fox only fortified his persona as a dissident member of the power élite.

In declaring war on the upper class that made him, Carlson joined a long, volatile lineage of combatants against the élite. From the beginning, the United States has had a vexed relationship to distinctions of status—a by-product of what Trollope called our “fable of equality.” Americans tend to root for the adjective (“élite Navy SEALs”) and resent the noun (“the Georgetown élite”).

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

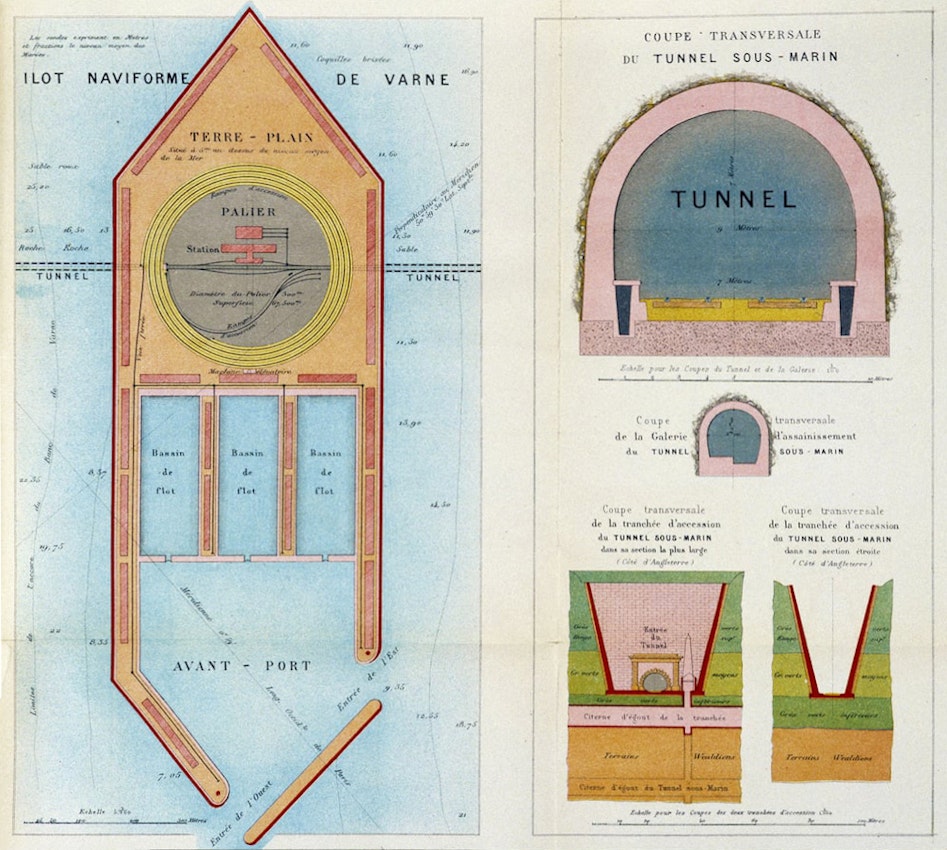

Thomé de Gamond’s plans for an underwater tunnel between England and France, produced for the World Exposition of 1867. The yellow circles, top left, represent an enormous spiral ramp allowing access to the tunnel from an international artificial island on the Varne sandbank — Source.

The English Channel (la Manche, “the sleeve”, to the French) is one of the roughest sea crossings in the world. At its narrowest, in the Strait of Dover, it is a mere twenty miles across, but for those attempting the crossing this brevity is of little comfort. The Strait’s shallowness, combined with its unique tidal streams, ocean currents, and regular fog, make for a turbulent and hazardous journey, and the sea sickness it induces is notorious.

For centuries, the Channel was Britain’s bulwark against foreign invasion. The vicious weather was given a divine interpretation as the “protestant wind” which sunk the Spanish Armada in 1588. But this was a double-edged sword: merchant shipping was as vulnerable as Phillip II’s great fleet. With the industrial era came peace and increased trade, and by the early nineteenth century the UK was the largest producer of manufactured goods in the world. Improvements in shipping and port facilities greatly facilitated trade, but the logistical problem of transferring goods from ship to shore remained. Unsurprisingly, faced with this issue, thoughts began to turn toward methods of avoiding the water altogether. In 1785, the trip was first made by balloon, but the first aeroplane would not follow until 1909. In 1851, a telegraph wire linked London and Paris directly. Might it be possible for a railway to follow? Many engineers believed it was: they proposed a tunnel, joining the roads and railways of Britain to those of mainland Europe.

But this was not simply a problem of engineering and geology. The idea of a fixed link was deeply intertwined with the issue of how the British understood international relations and their place in Europe during the age of imperialism. On the one hand stood those who believed in a shared European liberalism, founded on a belief in “the people” and the unifying power of international communications and free trade. For these champions of progress, great railway projects represented the spirit of the age: iron rails “knitting together the hearts of nations”, as one proponent would put it. Opposing this were Britons of a more pessimistic and suspicious disposition, who regarded Europe as permanently riven by diplomatic, military, and imperial tensions. For them, railways were a weapon, and the proposed channel tunnel a military frontier, exposing their wealthy and unprepared island to the massed armies of mainland Europe. It was this clash of worldviews, not the engineering challenge, that would decide the fate of the project.

Read the rest of this article at: The Public Domain Review

When Eleanor Coppola went into labor with her third child, on May 14, 1971, at a hospital in Manhattan, her husband, the director Francis Ford Coppola, was on location in Harlem, shooting a scene for “The Godfather.” Hearing the news, he grabbed a camcorder from the set and raced over to capture the moment. “When they say, ‘It’s a girl,’ my dad gasps and nearly drops the camera,” Sofia Coppola told me recently, of her birth video. “My mom is there, just trying to focus.” The footage—which has been screened by the family multiple times over the years, and as part of a feminist art installation designed by Eleanor—was the first of many instances in which Sofia would be seen through her father’s lens. When she was just a few months old, Francis cast her in her first official film role, as the infant in the dénouement of “The Godfather,” in which Michael Corleone, the ascendant boss of the Corleone crime family, anoints the head of his newborn nephew as his associates murder rival gangsters one by one.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

People have had opinions about Maggie Ervie’s body ever since she was a baby. Maggie, who is 15 years old, has lived her whole life in Marceline, Missouri, a town of just more than 2,000 people 97 miles northeast of Kansas City, reached by driving straight highways that traverse wide cornfields lined by white fences, past sale lots full of shiny blue tractors. Walt Disney spent his boyhood in Marceline, and Mark Twain’s hometown is not far away. The people of Marceline — many descended from farmers, railroaders, and coal miners — have grown up together, as did their parents and grandparents, which makes them a little more comfortable expressing themselves about one another’s business.

When Maggie was still in diapers, a relative leaning over her changing table made a comment to her mother, Erika, about how her “cha cha” was chubby, and when she was in preschool, the playground chaperone would regularly send Erika photos of Maggie’s behind — on the jungle gym, on the merry-go-round — because her jeans, wide at the waist to accommodate her belly, would slip down her hips when she played. In retrospect, Erika can see how the playground monitor might have thought the pictures were cute or funny, but because Erika had been heavy as a child herself, they landed in her texts like taunts. “There’s Maggie’s little booty crack here and there and everywhere,” she recalls. It was hard to find clothes that fit Maggie; Erika had to drive to Kansas City or place special orders at Gymboree and the Children’s Place. When Maggie graduated from kindergarten, her pink ceremonial gown wouldn’t zip up all the way, so the teacher had all the children attend graduation with their gowns open. By elementary school, she had settled on a uniform of leggings and tunics.

Over time, people began to direct their opinions toward Maggie herself, as on the day in fifth grade when everyone had to come to school wearing clothes that represented the Kansas City Chiefs. Maggie, with nothing suitable in her closet, settled on her father’s 3XLT Chiefs shirt. It seemed good enough until one of her friends pointed out loudly that Maggie was wearing her father’s clothes to school, and Maggie, who is usually good-natured, came home crying. There were other times, as when a group of girls would see Maggie go back for seconds in the cafeteria and remark, “I’m so full. I couldn’t eat one more bite. I don’t know how you could eat all that.” But Maggie thought the lunch at school was delicious. She and the cook had a bond: Maggie loved to eat, and the cook, gratified, loved to give her more food.

In Missouri, at the edge of the Corn Belt and one of the leading beef-producing states in the nation, nearly 37 percent of adults are obese, slightly below the national rate. And in Marceline, weight loss is a way of life. At least eight of the Ervies’ friends or acquaintances have undergone bariatric surgery, and Erika can name a dozen people who are on Plexus — a “system” of powders, supplements, and creams that supposedly promotes muscle mass and gut-biome health. For a time, people were getting shots of vitamin B-12 and doses of phentermine from a doctor in town with a cash-only business, and everyone’s always trying keto or Herbalife. There are many larger children at Maggie’s high school, but even so, thinness conveys rank in the pecking order. Wrestling is a popular sport, for boys and for girls, and the athletes “cut weight” before meets by wrapping themselves in trash bags, spitting into a cup, and taking laxatives. Maggie knows a girl whose stepmother requires her to get on a scale before opening the fridge.

Read the rest of this article at: The Cut

Nearly 25 years ago, I reported on the changing demographics of Cicero, a working-class suburb just west of Chicago. For years, the town, which was made up mostly of Italian and Eastern European American families, worked hard at keeping Black people from settling there. In 1951, when a Black family moved in, a mob entered their apartment, tore it up, and pushed a piano out a window. Police watched and did nothing. The governor had to call out the National Guard. By 2000, the nearby factories, which were the economic foundation of the community, had begun to close. White families moved out and left behind a distressed, struggling town to its new residents—Latinos, who now made up three-quarters of the population. It felt wrong. It felt like the white families got to enjoy the prosperity of the place, and then left it to these newcomers to figure out how to repair aging infrastructure and make up for the lost tax revenues.

After reading Benjamin Herold’s Disillusioned, I now realize I was witnessing something much larger: the steady unraveling of America’s suburbs. Herold, an education journalist, set out to understand why “thousands of families of color had come to suburbia in search of their own American dreams, only to discover they’d been left holding the bag.” In this richly reported book, he follows five families that sought comfort and promise in America’s suburbs over these past couple of decades, outside Chicago, Atlanta, Dallas, Los Angeles, and Pittsburgh. In each of these communities, Herold zeroes in on the schools, in large part because education captures the essence of what attracted these families: the prospect of something better for their kids.

The racial and economic fissures in our cities have gotten much attention, but less has been written about how these same fault lines have manifested themselves in the suburbs. This is surprising because the suburbs serve as such a deeply powerful symbol for American aspiration. A house. Good schools. Safe streets. Plentiful services. Consider that from 1950 to 2020, the populations of the nation’s suburbs grew from roughly 37 million to 170 million, which Herold writes represents “one of the most sweeping reorganizations of people, space, and money in the country’s history.”

The suburbs have become such a strong emblem for the American dream that in the 2020 presidential election, Donald Trump used their decline as a bludgeon against the Democrats to suggest that that dream was withering. “They fought all their lives to be there,” he declared about suburbanites. “And then all of sudden something happened that changed their life.” He posted on Twitter, “If I don’t win, America’s Suburbs will be OVERRUN with Low Income Projects, Anarchists, Agitators Looters, and, of course ‘Friendly Protestors.’” I can’t fully decipher Trump’s rant, but suffice it to say he knew that people feared the fall of America’s great experiment in community, and he played off white families’ fear that their communities would be “overrun” with residents who didn’t look like them. In the granular details of the lives of the five families Herold chronicles, it’s clear that Trump had it only partially right. The suburbs—especially the inner-ring suburbs, those closest to the urban centers—have been in collapse, but the people affected, mostly Black and brown families, are not necessarily the constituency Trump had in mind.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic