Earlier this spring, I took the bus to the Moscone Center, in downtown San Francisco, where almost thirty thousand people had gathered for the annual Game Developers Conference (G.D.C.), which I was attending as a journalist. I had spent the previous few months out on maternity leave, and I was glad to return to work, to have meetings, to temporarily exit the domestic sphere. Participating in public life felt incredible, almost psychedelic. I loved making small talk with the bus driver, and eavesdropping on strangers. “Conferences are back,” I heard one man say, sombrely, to another. As my bus pulled away, I saw that it was stamped, marvellously, with an advertisement for Taiwanese grouper. “Mild yet distinctive flavor,” the ad read. “Try lean and nutritious grouper tonight.”

On the G.D.C. expo floor, skateboarders wearing black bodysuits studded with sensors performed low-level tricks on a quarter-pipe. People roped with conference lanyards stumbled about in V.R. goggles. Every wall or partition seemed to be covered in high-performance, high-resolution screens and monitors; it was grounding to look at my phone. That week, members of the media and prolific tech-industry Twitter users couldn’t stop talking to, and about, chatbots. OpenAI had just released a new version of ChatGPT, and the technology was freaking everyone out. There was speculation about whether artificial intelligence would erode the social fabric, and whether entire professions, even industries, were about to be replaced.

The gaming industry has long relied on various forms of what might be called A.I., and at G.D.C. at least two of the talks addressed the use of large language models and generative A.I. in game development. They were focussed specifically on the construction of non-player characters, or N.P.C.s: simple, purely instrumental dramatis personae—villagers, forest creatures, combat enemies, and the like—who offer scripted, constrained, utilitarian lines of dialogue, known as barks. (“Hi there”; “Have you heard?”; “Look out!”) N.P.C.s are meant to make a game feel populated, busy, and multidimensional, without being too distracting. Meanwhile, outside of gaming, the N.P.C. has become a sort of meme. In 2018, the Times identified the term “N.P.C.” as “the Pro-Trump Internet’s new favorite insult,” after right-wing Internet users began using it to describe their political opponents as mechanical chumps brainwashed by political orthodoxy. These days, “N.P.C.” can be used to describe another person, or oneself, as generic—basic, reproducible, ancillary, pre-written, powerless.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

The brain-powered individual, which is variously called the self, the ego, the mind, or “me,” lies at the center of Western thought. In the worldview of the West, we herald the greatest thinkers as world-changers. There is no more concise example of this than philosopher René Descartes’ famous statement, “Cogito, ergo sum,” or, “I think, therefore I am.” But who is this? Let’s take a closer look at the thinker, or the “me,” we all take for granted.

This “I” is for most of us the first thing that pops into our minds when we think about who we are. The “I” represents the idea of our individual self, the one that sits between the ears and behind the eyes and is “piloting” the body. The “pilot” is in charge, it doesn’t change very much, and it feels to us like the thing that brings our thoughts and feelings to life. It observes, makes decisions, and carries out actions — just like the pilot of an airplane.

This I/ego is what we think of as our true selves, and this individual self is the experiencer and the controller of things like thoughts, feelings, and actions. The pilot self feels like it is running the show. It is stable and continuous. It is also in control of our physical body; for example, this self understands that it is “my body.” But unlike our physical body, it does not perceive itself as changing, ending (except, perhaps for atheists, in bodily death), or being influenced by anything other than itself.

Read the rest of this article at: Big Think

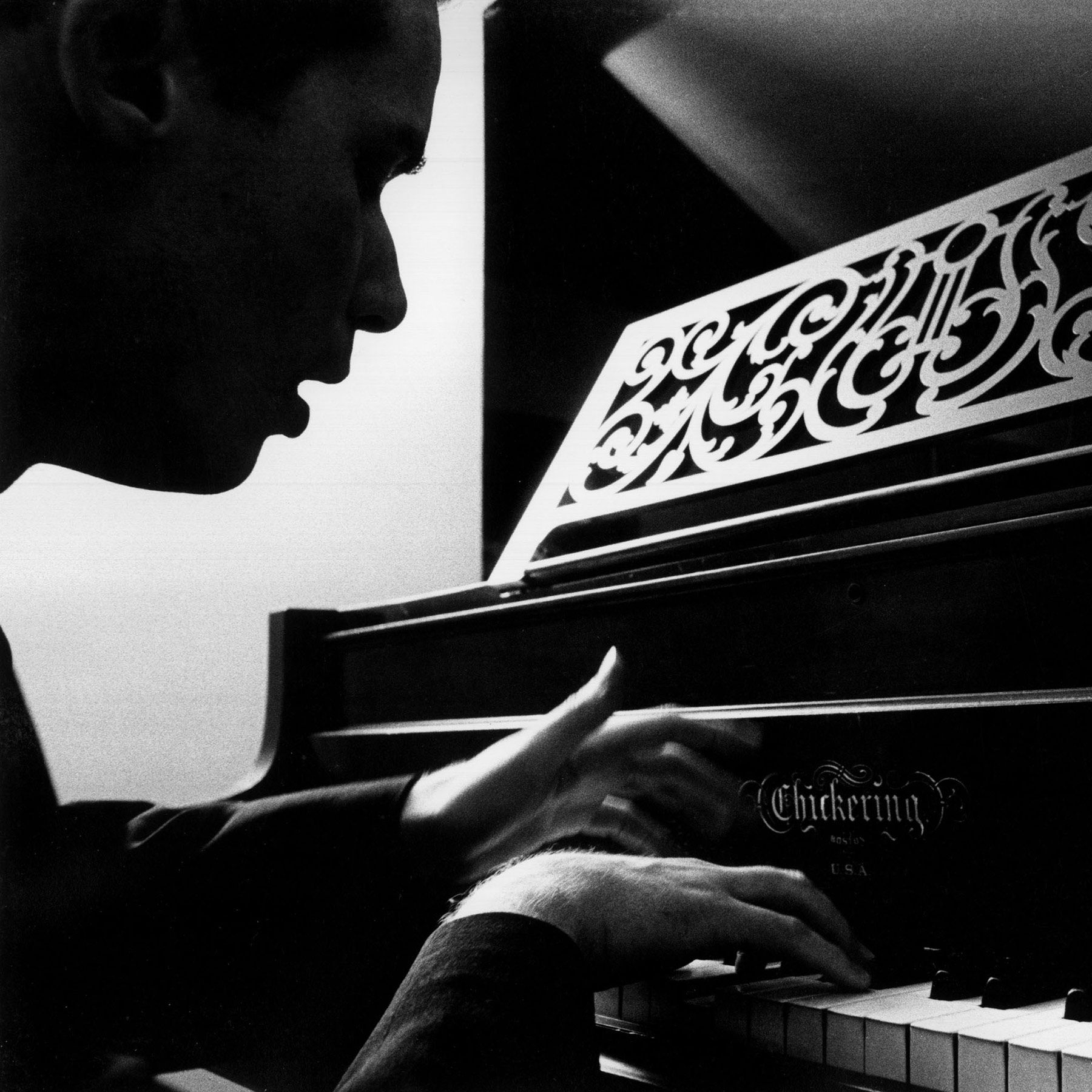

The number of musical genres is bewilderingly vast and, thanks to digital technology, music of every sort is available to you with a few clicks or taps. So why, in this sea of sound, should you get to know more about classical music?

Well, there is no form of music that you need to know. Listening to classical music is not a duty, though well-intentioned advocates have sometimes made it seem like one. But there are good reasons you might want to explore classical music. Classical music can be exciting, absorbing, emotionally moving, inspiring, challenging, thought-provoking and often simply astonishing. Why wouldn’t you seek out all that? And, if you found it, wouldn’t the want feel like a need?

In this Guide, I invite you to discover all these qualities for yourself. The recommendations I’ll offer can help enrich your experience of classical music, whether you are a newcomer to the genre or a long-time listener.

I fell in love with classical music a long time ago, as a teenager growing up in New York. One of my happiest memories of that time involves trips to the library to borrow vinyl records in the company of others doing the same, people of all ages, ethnicities and races, bound together by a shared desire for those enthralling sounds. The feeling of spontaneous community prevailed. Preferences passed from person to person in library whispers. It just felt good to be there.

Read the rest of this article at: Psyche

On September 21, 2021, my mother sent a message to my extended family’s WhatsApp group: “Neeti had a heart attack and suddenly passed away—too tragic!” Neeti was a daughter of her sister, and someone I’d known all my life. But my cousin and I inhabited different worlds. I was born and raised in suburban New Jersey; she was a lifelong Delhiite. To me, Neeti and her identical twin, Preeti, exuded an urban glamour. At weddings, they sported chic, oversized sunglasses and matching, pastel-colored Punjabi-style outfits. Their faces looked a lot like my mom’s: long, with prominent cheekbones and almond-shaped eyes. Where Preeti was garrulous and expressive, though, Neeti was quieter, more guarded, more likely to keep her struggles to herself.

Could she really have had a heart attack? We all found that strange. Neeti was known in the family as a fitness freak. At the age of forty, the mother of two, she taught yoga and regularly spent time in the gym. When the Hindi-language television channel ABP News reported her death, it chose to represent her with clips of her working out—jump-squatting, doing pushups with her hands balanced on dumbbells.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

On a recent Thursday afternoon at SJP Collection, a tiny, pink, candle-scented shoe boutique in Manhattan’s West Village, the store’s owner, the fifty-eight-year-old actress Sarah Jessica Parker, was working the floor. “Stuff the toes with this,” she said, holding a wad of tissue paper up to a bride-to-be who was wedding-shoe shopping with her mother. The young woman had selected a pair of white lace Cosettes ($450), a heeled Mary Jane with a rhinestone buckle. Parker was eagerly explaining how to store them between wears. She had on the same design along with her everyday “uniform,” a studiously distinctive take on jeans and a T-shirt: 7 for All Mankind denim, a cotton top that she cuts at the neckline and ruches with safety pins, and a charm necklace twisted through the strap of her bra so that the chain falls at her left breast, like an eccentrically long lapel pin. Her highlighted blond hair was pulled back into a tight chignon. She packed the Cosettes into a box and handed them to the women.

“Wear these in good health!” she said, doing the slightest curtsy.

Parker remains best known for her role as Carrie Bradshaw, the twinkly sex columnist in the HBO series “Sex and the City,” who had a lustier relationship with Manolo Blahniks than with most of the men she dated. Parker recalled that, when the series concluded after six seasons, in 2004, financiers began “backing up the money trucks,” asking her to put her name on a line of shoes. She was not against branding opportunities—a clothing line with the now defunct retailer Steve & Barry’s, a fragrance called Lovely—but she considered stilettos a taller order. “I felt honor-bound to produce shoes that I would wear,” she said. When she started SJP Collection, in 2014, she partnered with George Malkemus III, who’d helped popularize Manolo Blahniks as the brand’s U.S. president, and insisted that the shoes be handmade in Italy. In 2021, Malkemus III died, and though Parker has never taken a “single penny” of salary from the company, she continued designing the shoes herself.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker