Not long ago, I was preparing to interview Tom Hanks at Symphony Space, a theatre on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, for an audience of seven hundred-plus people at The New Yorker Live. Hanks had just published a novel called “The Making of Another Major Motion Picture Masterpiece,” and he was hitting the road for a while. Symphony Space was the first stop on the tour. Someone from Knopf, his publisher, let me know that I would embarrass Hanks if, in my introduction, I went through the litany of movies he has starred in since the early eighties. In fact, if I had, that would have been the whole evening. The list is long and shimmery. Hanks is that rare thing, a real movie star who has sustained a four-decades-and-counting career. It’s not just that he has won two Oscars in a row (for “Philadelphia” and “Forrest Gump”) or made box-office hits including “Splash,” “Saving Private Ryan,” and Steven Spielberg’s most enjoyable film, “Catch Me If You Can.” He’s also capable of taking on a predictable vehicle, such as the recent feature “A Man Called Otto,” and pumping some life into it while attracting a sizable audience.

What surprised me is the degree to which Hanks, particularly in front of a live crowd, in no way resembles Jimmy Stewart, the laconic Hollywood icon to whom he’s most often, and most lazily, compared. When we met beforehand, then onstage for an hour and a half, and, finally, over a long dinner at a local Greek restaurant, Hanks was about as laconic as Muhammad Ali. Or a hand grenade. He is funny, sarcastic, self-knowing, and a tireless raconteur, particularly about his day job. In our interview, he sometimes answered questions as he might in a more private setting than Symphony Space; far more often, he took some element of the question as a cue for a prolonged, well-polished anecdote, performed at the edge of his seat. Hanks’s novel is all over the place at times, undisciplined and overstuffed, but it contains extended passages and set pieces describing how movies are made that are entirely worth the ticket.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

Within minutes of my decision to hand my life over to AI, ChatGPT suggested that, if able, I should go outside and play with my dog instead of work. I had asked the chatbot to make the choice for me, and it had said that I should prioritize “valuable experiences” that contribute to my “overall well-being.” This instruction was welcome, as it was beautiful outside and, more importantly, not even noon on Monday, so I dutifully did as I was told.

After 35 years of living in relative control of my decisions, I had decided to see what would happen if I asked AI to control my life instead. Years of suboptimal performance, both personally and professionally, and numerous failed attempts at self-improvement had convinced me there had to be a better way, and I wondered if the collective knowledge hidden inside OpenAI’s hit tech product could help me. But when I asked Sam Altman’s ChatGPT to become my all-powerful leader, it seemed reticent, at least at first.

“While I appreciate your willingness to explore new possibilities, I must emphasize that I cannot truly take control of your life or make decisions on your behalf,” ChatGPT said as it ominously labeled our conversation “Control Your Life.” As someone who was hoping to have his entire life controlled by AI, I found the answer frustrating. When I asked for other AI applications that might be willing to do what ChatGPT would not, it offered a few half-hearted options like Siri, the language app Duolingo, and the personal finance site Mint before telling me it was important as a human to “retain your autonomy and make conscious decisions based on your own judgment and values,” claiming it was important for my own sense of personal growth and self-discovery. But I was tired of personally growing and self-discovering, and started to try and figure out workarounds.

Read the rest of this article at: Vice

A couple of summers ago, I went to the Guinness Storehouse in Dublin. I’d spent a lot of time in the city before, but I’d never visited the brewery. The tour is good. You can learn about how barrels are made, get your face printed in the head of a pint and, at the end, have a drink in a bar with a 360-degree view of the city. But what stayed with me most was something I saw there by accident.

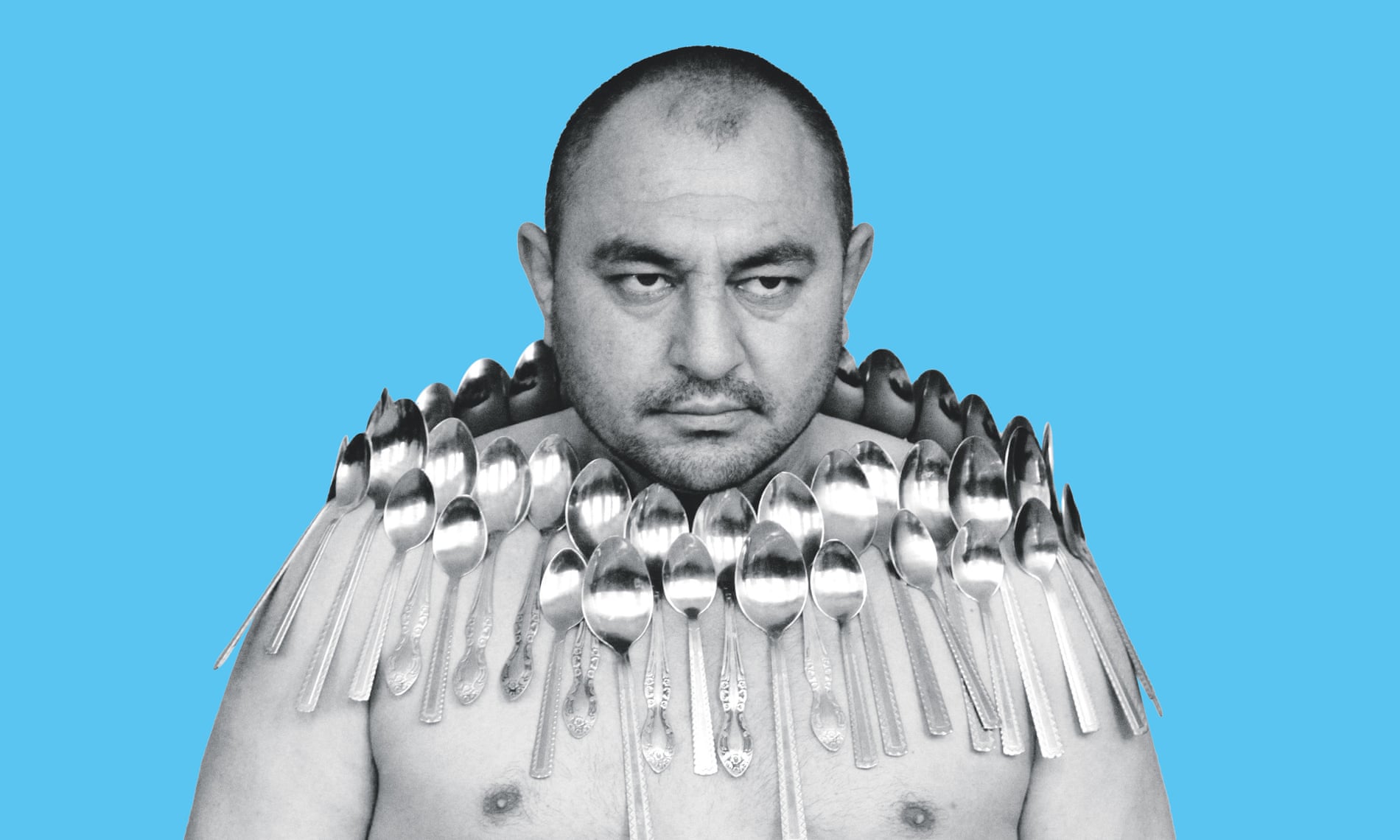

One of the exhibit rooms was closed off, but only partially. Curiosity got the better of me, and behind the door, I found a room that was empty but for a table. On the table, there were a handful of editions of the Guinness Book of Records. I hadn’t thought about this book since I was in primary school. Back then, the Guinness Book of Records meant a big, brightly coloured, hardback volume containing 500-odd pages of pictures of people doing things like growing their hair very long or juggling knives. These were books that children gleefully unwrapped on Christmas Day and argued over with their siblings. As I flicked through the old editions – 1994, 2005, 2012 – I thought about the connection between Guinness the stout and Guinness the book for the first time, as well as a hundred questions I hadn’t thought to ask as an eight-year-old marvelling at the man with the stretchiest skin or the most needles inserted into his head.

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian

Simi Cagilaba could hear the fighting outside his cabin door. In the hallway of the 209-foot tuna seiner, drunken crewmen were roiling the ship yet again. It was late, and the vessel was bobbing on the currents of the South Pacific, the fighting typical of nights when the cook let the crew drink the rice wine. Now, the unwelcome clamor moved toward his door like another bad omen in a trip that was steadily devolving.

An official observer of marine fisheries, Cagilaba was miles offshore of the Marshall Islands, dispatched aboard the seiner then known as the Sea Quest. It was 2015. He had a background in marine affairs and was working for the Fijian government in its national Ministry of Fisheries, tasked with upholding a patchwork of regulations meant to safeguard tuna.

Read the rest of this article at: Civil Eats

For a long time, Quentin Tarantino has spoken of his plan to walk away from filmmaking on his own terms—after making ten features, and by the age of sixty—while he still has plenty of vigor to devote to other kinds of work. He just reached sixty, and, having made his first nine films (he lumps the two “Kill Bill” installments together as one), he’s already at work on the tenth and, presumably, last, which is tentatively titled “The Movie Critic.” The movie-centric subject suggests a follow-up to his previous film, “Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood”; he says that it will be set in 1977, but denied rumors that it would be about the longtime New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael. (He says that the critic will be male.)

If Tarantino follows through on his planned exit from directing films, he’ll join élite company; it’s hard to think of notable directors who’ve preceded Tarantino in ending their careers voluntarily. Perhaps the greatest to have done so is Douglas Sirk, the German filmmaker, born in 1897, who immigrated to the United States; signed his first Hollywood contract, in 1942; and made his name there, in the nineteen-fifties, with melodramas such as “All That Heaven Allows,” “Written on the Wind,” and the remake of “Imitation of Life.” At the height of his success, in 1959, he ended his studio contract and returned to Europe, simply because, he said, he “had had enough” of Hollywood. It’s far more common for great directors to have their careers truncated by commercial ostracism, to be put out to pasture far too early because their movies were expensive and their box-office returns deemed inadequate—that cohort includes Buster Keaton, D. W. Griffith, Erich von Stroheim, Orson Welles, and Elaine May. (Josef von Sternberg’s withdrawal from Hollywood, in the early nineteen-fifties, seems to have been a case of mutual exasperation.) Also, some of the great Black directors who’ve made illustrious starts have often run up against an impenetrable wall of white producers blocking their subsequent movies. Such first-rate filmmakers as Christopher St. John, Wendell B. Harris, Jr., and Julie Dash have been unable to make more than one dramatic feature.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker