For residents of southeast Paris, the construction vehicles rumbling back and forth behind the Austerlitz train station are a loud annoyance that has gone on for too many months. But for city officials—and countless Parisians, they hope—history is unfolding behind the cordoned-off area. After years of thwarted ambitions and vague promises, the French capital, officials say, is set to accomplish a rare feat for a major metropolis: making its once heavily polluted waterway fit for swimming again.

In February, city officials invited TIME to pass through the metal turnstile behind the cordon, and see up close the cleanup of the Seine—one of the world’s most iconic rivers—which stretches for 481 miles, from Burgundy through Paris out to the sea in Normandy. Indeed, the river has defined Paris since it was founded by ancient Romans. It was along these riverbanks that merchants in the Middle Ages first set up, creating a settlement that finally dwarfed once bigger rivals like Lyon and Marseilles.

And it was on the banks, too, that the world’s finest architects constructed the Eiffel Tower, the Notre Dame Cathedral, and the Louvre and Orsay museums—stunning monuments that draw millions of visitors each year to sail down the narrow stretch of the Seine that cuts through the dead center of Paris. Officials are therefore keenly aware of the deeper significance of cleaning up the Seine, seeing it as a way of connecting the modern city to its oldest history. “The Seine,” says Emmanuel Grégoire, deputy mayor of Paris in charge of urban planning, “is the reason why Paris was born.”

Read the rest of this article at: Time

Happiness in intelligent people is the rarest thing I know,” an unnamed character casually remarks in Ernest Hemingway’s novel The Garden of Eden. You might say that this is a corollary of the much more famous “Ignorance is bliss.”

The latter recalls phenomena such as the Dunning-Kruger effect—in which people lacking skills and knowledge in a particular area innocently underestimate their own incompetence—and the illusion of explanatory depth, which can prompt autodidacts on social media to excitedly present complex scientific phenomena, thinking they understand them in far greater depth than they really do.

The Hemingway hypothesis, however, is less straightforward. I can think of a lot of unhappy intellectuals, to be sure. But is intelligence per se their problem? Happiness scholars have studied this question, and the answer is—as in so many parts of life—it depends. The gifts you possess can lift you up or pull you down; it all depends on how you use them. Many people see intelligence as a way to get ahead of others. But to get happier, we need to do the opposite.

You might assume that intelligence—whether it be the conventional IQ kind, emotional intelligence, musical talent, or some other dimension along which a person can excel—raises happiness, all else being equal. After all, people with higher cognitive ability should logically have more exciting life opportunities than others. They should also acquire more resources with which to enhance their well-being.

In general, however, there is no correlation between general intelligence and life satisfaction at the individual level. That principle does mask a few wrinkles. In 2022, researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine and Fordham University looked at the association between well-being and various building blocks of neurocognitive ability: memory, processing speed, reasoning, spatial visualization, and vocabulary. The only components of intelligence that they found to be positively related to happiness were spatial visualization, memory, and processing speed—but those relationships were fleeting and age-related.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

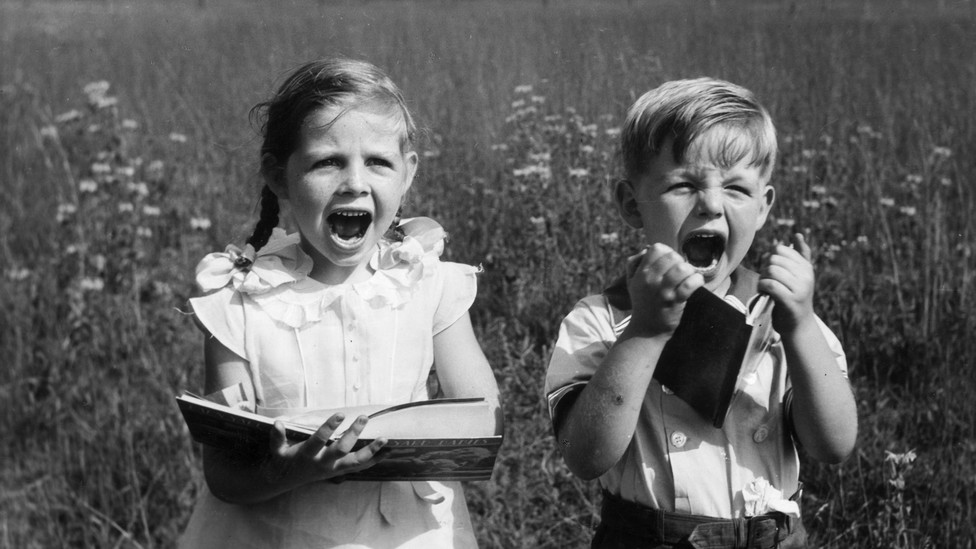

These days, when I explain to a fellow parent that I write novels for children in fifth through eighth grades, I am frequently treated to an apologetic confession: “My child doesn’t read, at least not the way I did.” I know exactly how they feel—my tween and teen don’t read the way I did either. When I was in elementary school, I gobbled up everything: haunting classics such as The Witch of Blackbird Pond and gimmicky series such as the Choose Your Own Adventure books. By middle school, I was reading voluminous adult fiction like the works of Louisa May Alcott and J. R. R. Tolkien. Not every child is—or was—this kind of reader. But what parents today are picking up on is that a shrinking number of kids are reading widely and voraciously for fun.

The ubiquity and allure of screens surely play a large part in this—most American children have smartphones by the age of 11—as does learning loss during the pandemic. But this isn’t the whole story. A survey just before the pandemic by the National Assessment of Educational Progress showed that the percentages of 9- and 13-year-olds who said they read daily for fun had dropped by double digits since 1984. I recently spoke with educators and librarians about this trend, and they gave many explanations, but one of the most compelling—and depressing—is rooted in how our education system teaches kids to relate to books.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

JAMES BRIDLE IS sitting in an old stone courtyard, radiantly tan, a silvery-green olive tree over their shoulder. In the distance, dry hills curve towards a sky blue with songbirds and distant bells. It’s precisely the scene I imagined I’d see, reaching the writer at home in Aegina. Bridle moved to this Greek island in early 2020, a big change in a year of even bigger changes, and it’s here, in this dappled courtyard, that they wrote Ways of Being, published by Farrar, Strauss & Giroux in June.

“I’m just very, very lucky to have been able to work and to think here,” they tell me. Ways of Being is a meditation on artificial intelligence’s place in a more-than-human world, and Greece — alive, ancient, and all watched over by loving satellites — is omnipresent. In the book, Bridle drives a home-brewed autonomous vehicle up the slope of Mount Parnassus; they trace how AI is used to identify oil drilling sites in remote Epirus; they harvest metal-accumulating plants in the Pindus mountains. In one of the book’s loveliest passages, swallows swooping over Aegina’s abandoned beaches signal the coming of spring, even in the midst of a pandemic. Everything is connected. Speaking of computers and mythology alike, Bridle summons oracles.

Read the rest of this article at: Grow

Until last summer, we had a dead frog in our freezer. When Bunky died, George and I thought we should wait to bury him till both our grown children were home, so we put him in a Ziploc bag and propped him on his side on a shallow shelf in the freezer door, just above the icemaker. Bunky was flat and compact and, very soon, as rigid as a cell phone. He fit perfectly. I’d always wondered what KitchenAid intended that shelf for—it was too narrow for any food I could think of—but now we knew. It was intended to hold a frog.

There are two kinds of pets—the ones you choose and the ones that happen to you. Bunky belonged to the second category. He entered our family in the haphazard fashion of pets of that ilk: tadpole kit (cubical plastic “habitat” with domed top, like nave of Hagia Sophia, sans tadpole but accompanied by redeemable coupon), left by educational-toy-oriented grandmother for granddaughter under Christmas tree; kit sidelined for years on toy shelf; kit discovered by granddaughter’s preschool-age little brother; tadpole coveted; tadpole coupon redeemed by parents; tadpole shipped to New York City from Florida in Styrofoam container; tadpole universally admired for transparent skin (visibly beating heart!) and awesome metamorphosis (weird whiskers! hind legs! front legs! no more tail!); froglet admired somewhat less; adult frog mostly ignored, except by visiting small boys, who, if they didn’t have frogs themselves, paused to pay brief homage before moving on to Legos, and by owner’s father, who, despite initial intentions to teach son responsibility through pet care, ended up feeding frog (Stage Two Food Nuggets, meted out with tiny yellow Stage Two Food Serving Spoon dainty enough for fairy) and, once frog graduated from Hagia Sophia, cleaning aquarium, first two-gallon plastic, then four-gallon glass (challenging, because frog, coated with gelatinous goo, required apprehension and temporary relocation while aquarium was emptied, refilled, and doctored with dechlorinating crystals, and damn, was he slippery).

Read the rest of this article at: Harper’s Magazine