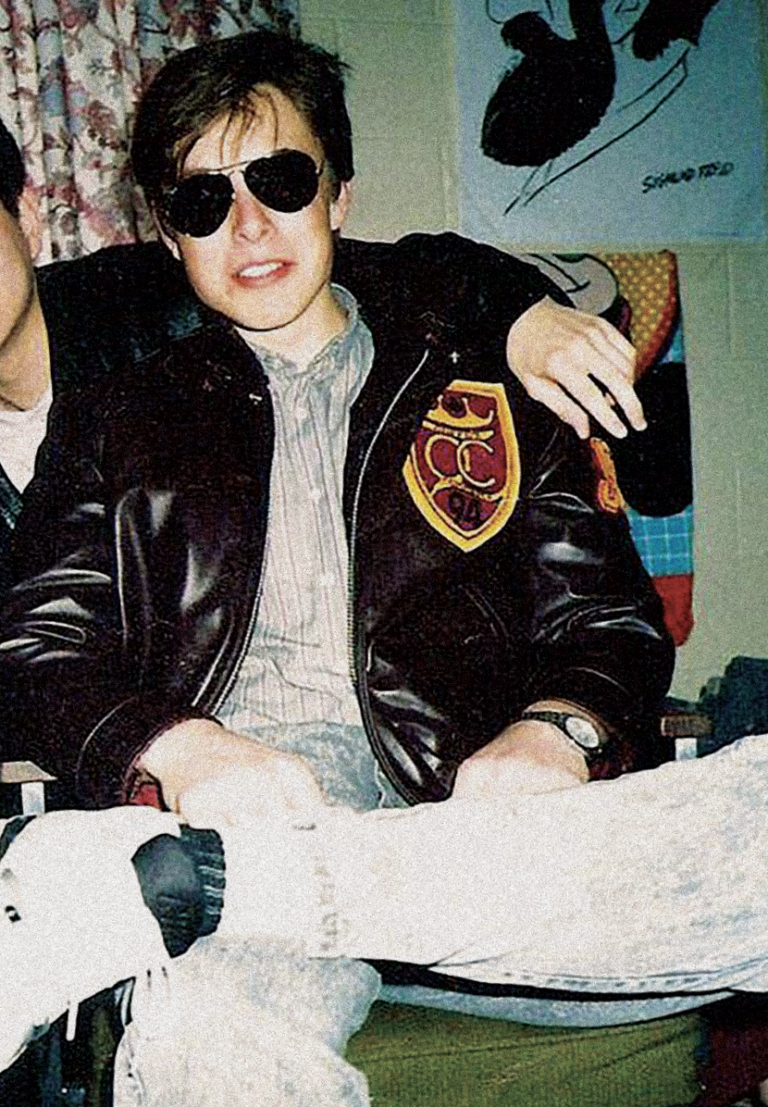

In some ways, he can’t help it. When a person is worth about $150 billion—making him, at age 51, one of the wealthiest individuals on the planet—people are bound to be curious. But Musk is also the type of guy who wants you to look. The type of guy who, in April 2022, struck a $44-billion deal to buy Twitter, bragged that he did it so he could “help humanity,” then spent the summer very publicly trying to get out of paying up. The type of guy who, two days before finally closing the headline-making purchase in late October, changed his Twitter bio to “Chief Twit” and posted a video of himself walking into the company’s San Francisco headquarters carrying a white porcelain sink, captioning it, with a resounding comedic thud, “Let that sink in!” And the type of guy who proceeded to ruthlessly jettison half of his inherited staff, ominously warning everyone else to work harder (something he calls “being hardcore”). Musk is so odd, so ambitious and so mercurial that it’s easy to forget he’s also brilliant. Can all of those extremes coexist in one human? Normally, no. But Musk is not normal. He’s earned nearly everything he has by being smart—and by possessing a lifelong, near-maniacal sense of self-belief.

Musk is like an alien doing his best impersonation of a human. Unsurprisingly, he has always been somewhat of an outcast. He was born in Pretoria, South Africa. His mother, Maye, was a dietician and model. (She’d go on to become a CoverGirl and appear in a Beyoncé video.) His father, Errol, was an engineer who worked in property development and emerald mining. Musk has said that he was raised first by books—particularly Isaac Asimov’s Foundation sci-fi series—and then by his parents. When he was eight, they divorced. Musk and his younger siblings, Kimbal and Tosca, went to live with Maye. By the time he was 10, he’d started to feel sorry for Errol, who seemed sad and lonely without his family. Musk decided to join his dad in Lone Hill, a suburb of Johannesburg. The move turned out to be a terrible mistake. Musk has since described his father as someone who “will plan evil.” Errol, in his defence, has said he’s been accused of many things, among them being a “rat” and a “shit,” but stresses that he loves his kids. (Musk once tried to mend things with his father as an adult, but it didn’t go well. He has since severed their relationship.)

Read the rest of this article at: Toronto Life

The rancher plucked the tiny tooth out of the sand of a dry creek bed. Around him was a grassy plain studded with low, flat hills. The small, dark object in his hand was worn down by use in life and by the water it had encountered over millennia. The tooth had long since petrified into stone.

Harold J. Cook had uncovered fossils in western Nebraska for much of his life. As a teenager in 1904, he led a paleontologist from Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum to a trove of early-mammal bones. The fossils practically tumbled from a hillside on his family’s ranch, known as Agate Springs. Among the bones were remnants of Dinohyus, an animal resembling a pig that stood as high as eight feet at the shoulder, and the still mysterious Moropus, a horse-like creature that dug in the earth with hooves that resembled claws.

The news that the Cooks’ land was bursting with the bones of ancient mammals set off a polite war among the leading natural history museums, which hoped to gain exclusive access to the fossil beds. Harold’s father, however, wanted the institutions to work together to wring all possible scientific knowledge from what would be known as the Agate Fossil Beds. He never profited from the treasure on his land. His family’s contributions to paleontology were celebrated in other ways: One scientist named an extinct rhinoceros in his honor, and an antelope with two of its four horns on its nose after young Harold.

Another scientist, Henry Fairfield Osborn, lured Harold Cook to New York City to work at the American Museum of Natural History and to study with him at Columbia University. Cook returned home after a year to help run the ranch when his mother became ill. That meant he both knew the land and knew fossils, making him a valuable hire for any paleontology expedition in the region.

In 1917, the year the United States entered World War I, Cook assisted paleontologists from the Denver Museum and the American Museum in digs at fossil beds along Snake Creek, some 20 miles south of his family’s ranch. Whether he picked up the tooth while scouting for those excavations, during one of them, or sometime after, he never said. Broken bits of fossil, turned blue-black by iron phosphate, were common in the region, and had little scientific value compared with the bones of entire herds of pony-size rhinoceroses or the corkscrew-shaped dens of prehistoric beavers. But Cook believed he had found something truly special. Based on his knowledge of fossils, he suspected that the tooth belonged to a primate, and not a mere monkey—an ape perhaps. An even more tantalizing prospect was that the tooth belonged to an early human.

If Cook was right it would be a heady find, as scientists had yet to identify either variety of fossil in America. Meanwhile, paleontologists around the world were eager for evidence of so-called missing links—transitional fossils that could help prove that humans evolved from apes. Men who claimed to have found missing links often became famous.

Cook was correct about one thing: The tooth was important. But it would become part of history in a way he never imagined.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atavist Magazine

If you’ve ever emerged from the shower or returned from walking your dog with a clever idea or a solution to a problem you’d been struggling with, it may not be a fluke.

Rather than constantly grinding away at a problem or desperately seeking a flash of inspiration, research from the last 15 years suggests that people may be more likely to have creative breakthroughs or epiphanies when they’re doing a habitual task that doesn’t require much thought—an activity in which you’re basically on autopilot. This lets your mind wander or engage in spontaneous cognition or “stream of consciousness” thinking, which experts believe helps retrieve unusual memories and generate new ideas.

“People always get surprised when they realise they get interesting, novel ideas at unexpected times because our cultural narrative tells us we should do it through hard work,” says Kalina Christoff, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. “It’s a pretty universal human experience.”

Now we’re beginning to understand why these clever thoughts occur during more passive activities and what’s happening in the brain, says Christoff. The key, according to the latest research, is a pattern of brain activity—within what’s called the default mode network—that occurs while an individual is resting or performing habitual tasks that don’t require much attention.

Read the rest of this article at: National Geographic

t had only snowed a dusting the day before, but my brother Jebsen had gone snowboarding at the local hill anyway. He and his friends had discovered a secret spot behind a small shopping plaza in Saugerties, New York, where they would build jumps on an undeveloped hillside in the woods. The packed piles of snow were more resistant to melting, so all they needed was a thin layer to freshen things up and they would disappear there for the day.

As my mother and I pulled up to the curb to pick him up, I noticed an unusual tiredness hung in his hunched shoulders. He had a dull stare that seemed to barely register our arrival, and his snowboard was sprawled halfway into the parking lot, as if he couldn’t be bothered to tend to it.

Slumping into the back seat, he complained of a headache. It came out a few miles down the road that he had hit his head on a rock and blacked out after going off one of the jumps. He said he wasn’t sure how long he was out for, but when he regained consciousness, he decided to shake it off and keep snowboarding with the guys for the rest of the day.

I could hear my mother’s deep inhalation, her eyes flipping up to assess him in the rearview mirror. “You probably have a concussion,” was her matter-of-fact assessment, masking the sudden tension that had set in. Back then, concussions were viewed as unfortunate but passing injuries, and Jebsen had many previous concussions that seemed to resolve just fine. Rather than view his prior record as a risk factor for more serious brain damage, it was easier to see it as evidence of resilience. “You should take it easy for a few days,” my mother said.

At a stoplight, however, we noticed something different this time. When my mother mentioned events of the previous day, Jebsen didn’t know what she was talking about. I laughed, thinking he was kidding, but when I swung my head back to exchange a smile with him, his face was slackened with confusion.

We volleyed back and forth on the way home, checking the big stuff first—names, people, places—until we homed in on the line that divided his intact memory from the events that had been swept clean: two weeks. The past two weeks of his life had been eroded at a sharp contact, like an underwater turbidity current that sweeps off the topmost sediment as it barrels downslope.

I was relieved that everything important, everything central to his identity, was still intact. On the surface, it seemed a minor loss, an otherwise mundane cache of daily routines. But it would be a lie to omit the unease I felt emanating from that scarp in his memory. It was like a sinkhole that suddenly pockmarks the ground; we rope it off with caution tape and cones, trying to reassure ourselves that the dangers have been safely delineated.

Read the rest of this article at: Nautilus

When I was in high school, I would lie in bed at night and think about how to outsmart a serial killer. The odds of my ever needing to do this seemed pretty slim, but I spent a lot of time thinking about it anyway. My plan, honed over many sleepless hours, was to talk to the killer enough to get him to see me as a person, or at least to distract him enough to hesitate and give me a chance to escape. Now I think I would have been better off focusing on learning to drive. I wanted freedom of movement, a chance to experience the world as if I were something other than a sweet treat waiting to be consumed, which was how I had been taught to see myself and everyone else: the two genders, eater and eaten. I wanted to feel like I could protect myself if I needed to, so I thought about how I could pacify the serial killers I would encounter, because as far as I knew, the only route to the things I wanted or needed was through soothing and circumventing an angry man. I was raised by an anxious mother and a domineering—see me avoiding the word abusive—father, and I grew up understanding that I was kept home and away from the world because it was full of men who wanted to hurt me; and that home was the domain of my father, a man who, at times, wanted to hurt me. And, as you can probably imagine, I have been confused ever since.

II.

In the fall of 2019, news outlets breathlessly announced that the FBI had identified a new serial killer, the most prolific in American history. His name was Samuel Little, and he had given up his story to a Texas Ranger named James Holland, who interviewed him after theorizing his connection to a cold case in Odessa, got a confession, and kept going. Little spent forty-eight days drinking Dr Pepper, eating pizza, and describing his murders to Holland. Then Holland described Little to the world: He was smart. He had a photographic memory. He had confessed to ninety-three murders. And he had evaded detection for so long, Holland told 60 Minutes, because “he was so good at what he did.”

I first heard about Samuel Little through this 60 Minutes segment, which introduced him, for anyone who lacked context, as the man who had committed “more [murders] than…Ted Bundy and Jeffrey Dahmer combined”; a “cunning killer” who “preyed upon…women he believed the police wouldn’t work too hard to find.” He drew portraits of his victims, and the FBI made them public in the hopes that they could be connected to more cold cases.

And I guess my first question—before I ask whether killing people within the wide swath of humanity that the police don’t care about actually means you’re smart, or means you’re just lucky because you’re gambling in a casino with the best odds in the world;[1] before I ask why we seemed to be so excited to have found not just a new serial killer but the most prolific one; before I ask why we use the word prolific so unthinkingly in this context, as if some serial killers are like J. D. Salinger and others are like Stephen King—my first question, still, is this: How are we even to know that Samuel Little had a photographic memory if almost all the women in his drawings look so much like one another? Why do so many of them have the same almond eyes, the same smokey eye makeup, the same face shape? Why did the seventy-nine-year-old man who happened to be the most prolific murderer in American history also happen to have one of the most impressive memories in American history? And if you’ve committed just a handful of murders—an unremarkable number, one that won’t even get you on the leaderboard—then wouldn’t it be, well, not a terrible idea to confess to a few dozen more? What if it makes you into something special, and helps the police close unsolved cases all over the country, and makes a great story for the people on TV, who will all want to talk to you now?[2]

Watching the first days of excited Samuel Little coverage, I thought: If it seems too good to be true, it probably is.

And then I wondered how the deadliest serial killer in American history could fall into the category of “too good to be true.”

Read the rest of this article at: The Believer