The “work from home” revolution has been very good for political columnists who like to write shirtless in pajama pants and share too much personal information with their readers. But the phenomenon hasn’t been so great for America’s cities.

The nation’s office buildings aren’t as empty as they were before COVID vaccines became widely available in spring 2021. But they’re still far less populated than they were in 2019. A recent analysis of Census Bureau data from the financial site Lending Tree found that 29 percent of Americans were working from home in October 2022. In New York City, financial firms reported that only 56 percent of their employees were in the office on a typical day in September.

Full-time remote work has grown less prevalent since the worst days of the pandemic. But flexible work arrangements — in which employees report to the office a couple times a week — are proving stickier. A recent paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research estimated that 30 percent of all full-time workdays would be performed remotely by the end of 2022.

As Insider’s Emil Skandul illustrates in an excellent piece, these surveys and projections are buttressed by mobile phone data showing that, in virtually all major U.S. cities, foot traffic in central business districts is down substantially from 2019.

Read the rest of this article at: New York Magazine

“Man is an invention of recent date. And one perhaps nearing its end.”

With this declaration in The Order of Things (1966), the French philosopher Michel Foucault heralded a new way of thinking that would transform the humanities and social sciences. Foucault’s central idea was that the ways we understand ourselves as human beings aren’t timeless or natural, no matter how much we take them for granted. Rather, the modern concept of “man” was invented in the 18th century, with the emergence of new modes of thinking about biology, society, and language, and eventually it will be replaced in turn.

As Foucault writes in the book’s famous last sentence, one day “man would be erased, like a face drawn in the sand at the edge of the sea.” The image is eerie, but he claimed to find it “a source of profound relief,” because it implies that human ideas and institutions aren’t fixed. They can be endlessly reconfigured, maybe even for the better. This was the liberating promise of postmodernism: The face in the sand is swept away, but someone will always come along to draw a new picture in a different style.

But the image of humanity can be redrawn only if there are human beings to do it. Even the most radical 20th-century thinkers stop short at the prospect of the actual extinction of Homo sapiens, which would mean the end of all our projects, values, and meanings. Humanity may be destined to disappear someday, but almost everyone would agree that the day should be postponed as long as possible, just as most individuals generally try to delay the inevitable end of their own life.

In recent years, however, a disparate group of thinkers has begun to challenge this core assumption. From Silicon Valley boardrooms to rural communes to academic philosophy departments, a seemingly inconceivable idea is being seriously discussed: that the end of humanity’s reign on Earth is imminent, and that we should welcome it. The revolt against humanity is still new enough to appear outlandish, but it has already spread beyond the fringes of the intellectual world, and in the coming years and decades it has the potential to transform politics and society in profound ways.

This view finds support among very different kinds of people: engineers and philosophers, political activists and would-be hermits, novelists and paleontologists. Not only do they not see themselves as a single movement, but in many cases they want nothing to do with one another. Indeed, the turn against human primacy is being driven by two ways of thinking that appear to be opposites.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

What gives you a sense of awe? That word, awe—the feeling of being in the presence of something vast that transcends your understanding of the world—is often associated with the extraordinary. You might imagine standing next to a 350-foot-tall tree or on a wide-open plain with a storm approaching, or hearing an electric guitar fill the space of an arena, or holding the tiny finger of a newborn baby. Awe blows us away: It reminds us that there are forces bigger than ourselves, and it reveals that our current knowledge is not up to the task of making sense of what we have encountered.

But you don’t need remarkable circumstances to encounter awe. When my colleagues and I asked research participants to track experiences of awe in a daily diary, we found, to our surprise, that people felt it a bit more than two times a week on average. And they found it in the ordinary: a friend’s generosity, a leafy tree’s play of light and shadow on a sidewalk, a song that transported them back to a first love.

We need that everyday awe, even when it’s discovered in the humblest places. A survey of relevant studies suggests that a brief dose of awe can reduce stress, decrease inflammation, and benefit the cardiovascular system. Luckily, we don’t need to wait until we stumble upon it; we can seek it out. Awe is all around us. We just need to know where to look for it.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

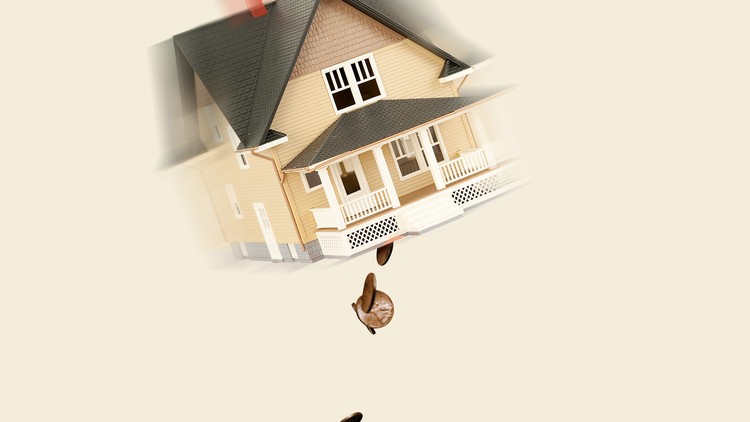

It is a truth universally acknowledged that an American in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a mortgage. I don’t know if you should buy a house. Nor am I inclined to give you personal financial advice. But I do think you should be wary of the mythos that accompanies the American institution of homeownership, and of a political environment that touts its advantages while ignoring its many drawbacks.

Renting is for the young or financially irresponsible—or so they say. Homeownership is a guarantee against a lost job, against rising rents, against a medical emergency. It is a promise to your children that you can pay for college or a wedding or that you can help them one day join you in the vaunted halls of the ownership society. In America, homeownership is not just owning a dwelling and the land it resides on; it is a piggy bank, where the bottom 50 percent of the country (by wealth distribution) stores most of its wealth. And it is not a natural market phenomenon. It is propped up by numerous government interventions, including the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage. America has put a lot of weight on this one institution’s shoulders. Too much.

The consensus that homeownership is preferable to renting obscures quite a few rotten truths: about when homeownership doesn’t work out, about whom it doesn’t work out for, and that its gains for some are predicated on losses for others. Speaking in averages masks the heterogeneity of the homeownership experience. For many people, homeownership is a largely beneficial enterprise, but for others, particularly young, middle-income and low-income families as well as Black people, it can be risky. This critique isn’t new (not even at this magazine); in fact way back in 1945, the sociologist John Dean summed up many of my concerns in this quote from his book Homeownership: Is It Sound?: “For some families some houses represent wise buys, but a culture and real estate industry that give blanket endorsement to ownership fail to indicate which families and which houses.”

Homeownership doesn’t even consistently deliver on the core promise of providing financial security. And, crucially, pushing more and more people into homeownership actually undermines our ability to improve housing outcomes for all.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic