The whirlwind surrounding “quiet quitting” first stirred in July when Zaid Khan, a twentysomething engineer, posted a TikTok of himself talking over a montage of urban scenes: waiting for the subway, looking up at leaves on a tree-lined street. “I recently learned about this term called quiet quitting, where you’re not outright quitting your job but you’re quitting the idea of going above and beyond,” Khan says. “You’re still performing your duties, but you’re no longer subscribing to the hustle-culture mentality that work has to be your life. The reality is it’s not. And your worth as a person is not defined by your labor.” The #quietquitting hashtag quickly caught fire, with countless other TikTokers offering their own elaborations and responses.

Traditional media outlets noticed the trend. Less than two weeks after the original video, the Guardian published an explainer: “Quiet Quitting: Why Doing the Bare Minimum at Work Has Gone Global.” A few days later, the Wall Street Journal followed with its own take, and the traditional financial media piled on. “If you’re a quiet quitter, you’re a loser,” the CNBC contributor Kevin O’Leary declared, before adding, “This is like a virus. This is worse than COVID.” Quiet-quitting supporters fought back, mostly with sarcasm. Soon after O’Leary’s appearance, a popular TikTok user named Hunter Ka’imi posted a video, recorded in the passenger seat of a car, in which he responds to the “older gentlemen” whom he had seen dismissing quiet quitting. “I’m not going to put in a sixty-hour workweek and pull myself up by my bootstraps for a job that does not care about me as a person,” he declares.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

The 1990s hadn’t gone as expected. A bad recession kicked off Gen X’s adulthood, along with a war in the Middle East and the fall of communism. Boomers came to power in earnest in America, and then the lead Boomer got impeached for lying about getting a blow job from an intern in the Oval Office. Grunge had come and gone, along with clove cigarettes and bangs. The taste of the ’90s still lingers, for those of us who lived it as young adults rather than as Kenny G listeners or Pokémon-card collectors, but the decade also ingrained a sense that expressing that taste would be banal, a fate that the writer David Foster Wallace had made worse than death (I swear he was cool once, along with U2).

Such was the crucible in which the computers were forged. Not the original computers—come on, give me some credit—but the computers whose reign still haunts us. Windows 3.0 arrived in 1990; the Mosaic web browser, Netscape’s precursor, in 1993; and Hotmail in 1996. I’m too tired to tell you the rest of the story, even though you’re probably too young or too old to fill in the blanks.

By 1999, the commercial internet had engorged into the dot-com bubble. The brick-and-mortar business world was going online—for information, for communication, for shopping, for utility billing. This moment had its own vocabulary: the information superhighway, the apostrophized ’net, and so on. E-business, we called it. (In a recent telephone call with a fellow old-timer, I used the word e-business tongue in cheek, and my interlocutor immediately dated my human origin to the early-to-mid-1970s.) The part of the internet that would persist got planted here, but we overharvested its fruits. Pets.com and Webvan, an early Instacart-type site, and so many more fell apart following the dot-com crash of 2000, ushering in a downturn that had turned further downward by 9/11 the following year.

People, trends, companies, culture—they live, and then they die. They come and go, and when they depart, it’s not by choice. Habituation breeds solace, but too much of that solace flips it into folly. The pillars of life became computational, and then their service providers—Facebook, Twitter, Gmail, iPhone—accrued so much wealth and power that they began to seem permanent, unstoppable, infrastructural, divine. But everything ends. Count on it.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

To give a sense of what it might be like to read Matthew Perry’s remarkable, startling, and heartfelt memoir, Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing, I’d like to share one particular reader’s experience:

A few months after completing the book, Perry was scheduled to record the audiobook version. That was when it struck him that although he had written the book—and he really had written it himself, double thumbing the first half in the Notes app on his phone before finishing the rest on his iPad—he had never actually allowed himself to read it from start to finish. The following day, he would be expected to perform these words into a microphone. Perhaps he should take steps to prepare himself. So he lay on his bed, iPad in front of him, and dove in.

Writing the book had felt freeing. “I was completely honest,” he says. “It just fell out of me. It just fell onto the page.” But this was the moment when its author discovered that it was one thing to have written the true story of Matthew Perry. It was quite another thing to read it.

“I read it,” he says, “and cried and cried and cried. I went, ‘Oh, my God, this person has had the worst life imaginable!’ And then I realized, ‘This is me I’m talking about.…’ ”

That night, Perry couldn’t even bear to be in the same room as his words.

“Because I had to go to sleep,” he says, “I actually took the iPad and put it outside my room. Because it was too close, too painful.”

Read the rest of this article at: GQ

My wife, Heidi, and I put up a string of Christmas lights early in the pandemic. They were LEDs that slowly flashed different colors, hung along a copper wire that stretched above our windows. As 2020 unfolded and we binged shows like Le Bureau, the lights made for a cheerful horizon. In the small East Village living room that became our world, it was a good trick. Before we stopped having people over, friends would comment on the vibe in our house. In the absence of company, vibe was all we had.

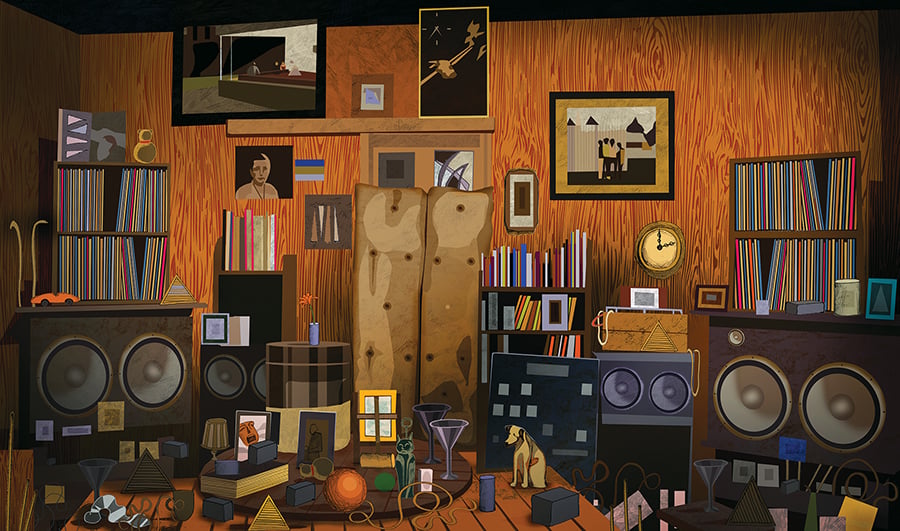

Right before the holidays, I discovered an Instagram account called @jazz_kissa, run by a photographer and music fan named Katsumasa Kusunose. Patrons of jazz kissas (cafés) typically drink coffee or alcohol and keep their voices low, sometimes reading books or comics as they listen. There are around six hundred such cafés in Japan—a number Kusunose and a few other fans carefully tabulated a few years ago, and which he believes has not significantly changed. Kusunose has been photographing these places since 2014, and his pictures became a ballast for me. The average jazz café is small, about the size of our living room, though a few are big enough to accommodate perhaps fifty people. Their audio gear generally looks older, and, even though I knew nothing about it, I decided it all sounded exquisite. A speculative leap, but I needed it.

Dim, atmospheric lights are not uncommon in jazz cafés, though most don’t look like our LED string. Sometimes the aquamarine glow of a McIntosh amp’s front panel is the only accent. There’s generally lots of wood, rarely any chrome or aluminum. If there is ever a human figure in Kusunose’s photographs, it is a man, usually older, laying a phonograph needle on a record or standing behind a pour-over coffee setup. I imagined that the stereos produced an otherworldly sound, and it did not seem unreasonable to think that these small spaces and our East Village safe haven were linked. The proprietors had made decisions about what mattered and what could be done with the limited space. Their choices emphasized an experience that would be both communal and quiet. Silence and sound at the same time appealed to me. What little we could control was right in front of us. We definitely didn’t have any of this gear, though. Our modest stereo would have been no better than a midrange system back in the Nineties, when it was new.

Read the rest of this article at: Harper’s Magazine

We are all products of our environments. This familiar phrase assumes that most of us spent our youth in one neighborhood, one delimited world. But I came of age in between spaces—a white kid with a single mother who filled my life with books and worried about making her salary last the month, and a father with severe mental illness in and out of institutions, I spent my adolescent nights on a rented floor of a two-family house and my days at the private junior high school that had waived my tuition. This boyhood geometry meant that I saw more of my city than I might have otherwise, which caused confusion, and eventually disbelief.

I grew up in late-1970s New Haven, Connecticut, a small, remarkably diverse city with a reputation for being a “representative” American urban setting. One way to think about childhood is as a succession of awakenings—moments of sudden, luminous clarity that say This is how the world is. I played a lot of baseball, which meant that as I progressed through the leagues, I roamed the city on my bicycle. In seventh grade at my new private school, many children had braces on their teeth. In the ensuing summer, I played shortstop near the projects in working-class Fair Haven, and one day, by second base, when a kid with a long Italian surname, whom we called “Rap,” showed glittering evidence of having visited the orthodontist, it occurred to me that here, among us, he was the only one.

Another year I played in Newhallville, a Black neighborhood not far from the failing Winchester gun factory, where I had teammates and opponents whose battered apartments and worn clothing suggested families struggling to meet their basic needs. One day I stood on the dusty field thinking about how right there, just up that hill and across a street named Prospect, the green lawns were kept lushly groomed for Yale University’s almost entirely white student body. It wasn’t just the divergent extremes I was absorbing, but their in-your-face proximity. The juxtaposition was bewildering enough to me then that I can still hear the strangely formal interior locution in which, my preadolescent voice not yet changed, I asked myself, Why should this be?

Newhallville is named for George Newhall, the owner of a carriage factory who needed expert hands so badly to keep up with his high volume of orders, he built housing for his workers. Eventually, the neighborhood industry shifted to the Winchester Repeating Arms Company. The Model 1873 was not “The Gun That Won the West,” as Winchester proclaimed, but a profusion of New Haven–assembled ordnance did help American soldiers prevail in two world wars, while providing a decent wage for people without a higher education. Factory labor was often tedious and physically draining, but members of every large European immigration wave lived in Newhallville, bought homes, and saw their children move out and up. Each arriving generation displaced or coexisted with the one that came before—Irish, Italian, German, Eastern European.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic