The Elle magazine article was a shocker. It went live a few days before Christmas and told a story of a journalist who lost her husband and her job because she fell in love with her source, who happened to be one of the most hated men on the planet, “Pharma Bro” Martin Shkreli. Why had Bloomberg News reporter Christie Smythe tossed away her “perfect little Brooklyn life” to pursue a seemingly doomed love affair with a sneering criminal known for jacking up medicine prices by 5,000 percent? And why had she then spilled her guts about it? I immediately wanted to dish about it. So did lots of other people. But in a pandemic, there are none of the usual gossipy gatherings.

Unless you were on Clubhouse.

Minutes after the story appeared, someone on Clubhouse had started a “room” to discuss it. Clubhouse, as you have no doubt heard, is an invitation-only audio social network that has drawn millions of people eager to socialize and listen in on an endless stream of conversations, as if all the text on Twitter, Facebook, and Interview magazine had acquired vocal cords. I joined the room titled “That Martin Shkreli Article” via the app on my iPhone, and my thumbnail profile photo was soon elevated from the “audience,” where people follow along as if listening to a podcast, to the “stage,” where you can unmute and contribute to the gabfest. I found myself among about a dozen people speculating about Smythe and the Pharma Bro. Maybe the whole thing was to solicit a movie deal? A scheme to help spring that nasty guy? We were talking out our asses.

Read the rest of this article at: Wired

Last summer a photograph of Syria’s First Lady circulated on social media. At the time, government troops in north-west Syria were battering the last pockets of rebel resistance to the regime. The picture showed Asma Assad, her husband Bashar al-Assad and their three children standing on a wind-swept hilltop, flanked by soldiers in camouflage. Bashar, dressed in an anorak, trainers and an untucked polo shirt, looks more suited to corralling the kids for a Sunday walk than torturing dissidents. Asma stands more stiffly, arms by her sides, wearing white jeans, trainers and the kind of aviator sunglasses beloved of Middle Eastern strongmen. She is at the centre of the photo; Bashar, president of Syria, hangs awkwardly at her shoulder.

The tranquillity of the landscape behind Asma is deceptive. Ten years on from the Arab spring, in which millions of people across the Middle East turned on repressive regimes, Syria’s ruling family has retained power – but at a terrible cost.

The regime’s forces have killed hundreds of thousands of Syrians, and tortured more than 14,000 people to death. Half the population have fled their homes, precipitating the greatest refugee crisis since the second world war. Iran and Turkey, as well as America and Russia, have fought proxy battles for influence on Syrian soil. Throughout the Arab world the hopeful dreams of a decade ago have been crushed, but nowhere more bloodily than in Syria.

Asma, however, is more powerful than she has ever been. Her journey to supremacy over this devastated land has been a winding one, and the road is littered with her many incarnations: a J.P. Morgan banker cutting late-night deals; the glamorous First Lady who thought social reform and sharp tailoring would modernise a pariah state; the Marie Antoinette of Damascus, shopping as her country burned; mother to the nation, battling cancer while her husband’s troops crushed insurgents.

Read the rest of this article at: The Economist

At first, Ahmad Muaddamani was a distant voice coming through my computer speakers: a fragile whisper from a hidden basement. When I made contact with him on Skype, on 15 October 2015, he hadn’t left Darayya in nearly three years. Located less than five miles from Damascus, his town was a sarcophagus, surrounded and starved by the regime. He was one of 12,000 survivors.

They had been under fire from Bashar al-Assad’s rockets, barrel bombs and even a chemical weapon attack for many months. Syria’s president had besieged the town since November 2012. Like many others, Muaddamani’s family had packed their suitcases and escaped to a neighbouring town. They begged him to follow. He refused – this was his revolution, his generation’s revolution.

He had joined one of the first demonstrations in Darayya calling for change, in 2011. He remembered everything about his “first time”: his heart on fire. Losing his voice from shouting slogans. The joy of being there. It was his first sensation of freedom.

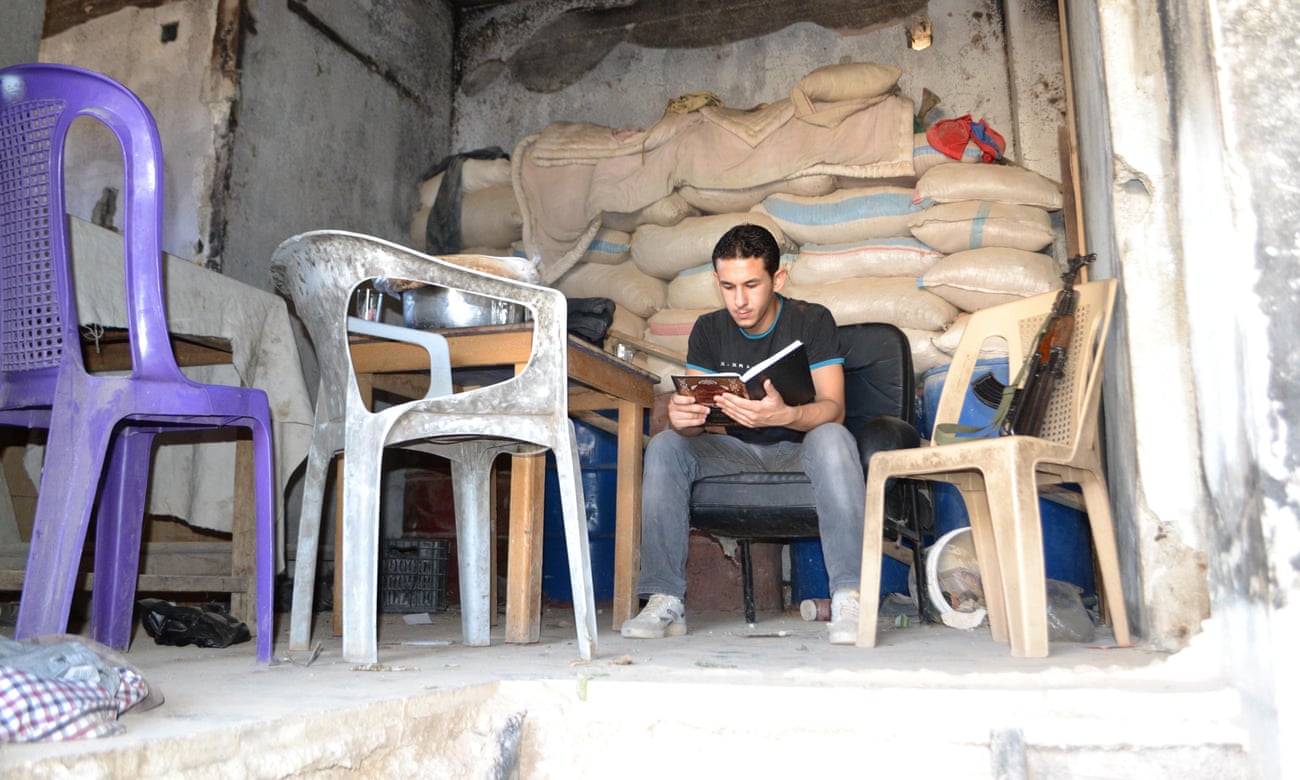

Muaddamani and other young rebels had stayed, not to defend their city, but to keep something in it alive. In the city under siege, he got hold of a video camera and finally realised his childhood dream: he would expose the truth. He joined the media centre run by the new local council. In the daytime, he roamed the devastated streets of Darayya. He filmed houses ripped apart, hospitals overflowing with the injured, burials for the victims, traces of a war invisible and inaccessible to foreign media. At night, he uploaded his videos to the internet.

One day in late 2013, Muaddamani’s friends called him – they needed some help. They had found books that they wanted to rescue in the ruins of an obliterated house.

“Books?” he repeated in surprise.

The idea struck him as ludicrous. It was the middle of a war. What’s the point of saving books when you can’t even save lives? He’d never been a big reader. For him, books smacked of lies and propaganda. After a moment of hesitation, he followed his friends through a gouged-out wall. An explosion had ripped off the house’s front door. The disfigured building belonged to a school director who had fled the city and left everything behind.

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian