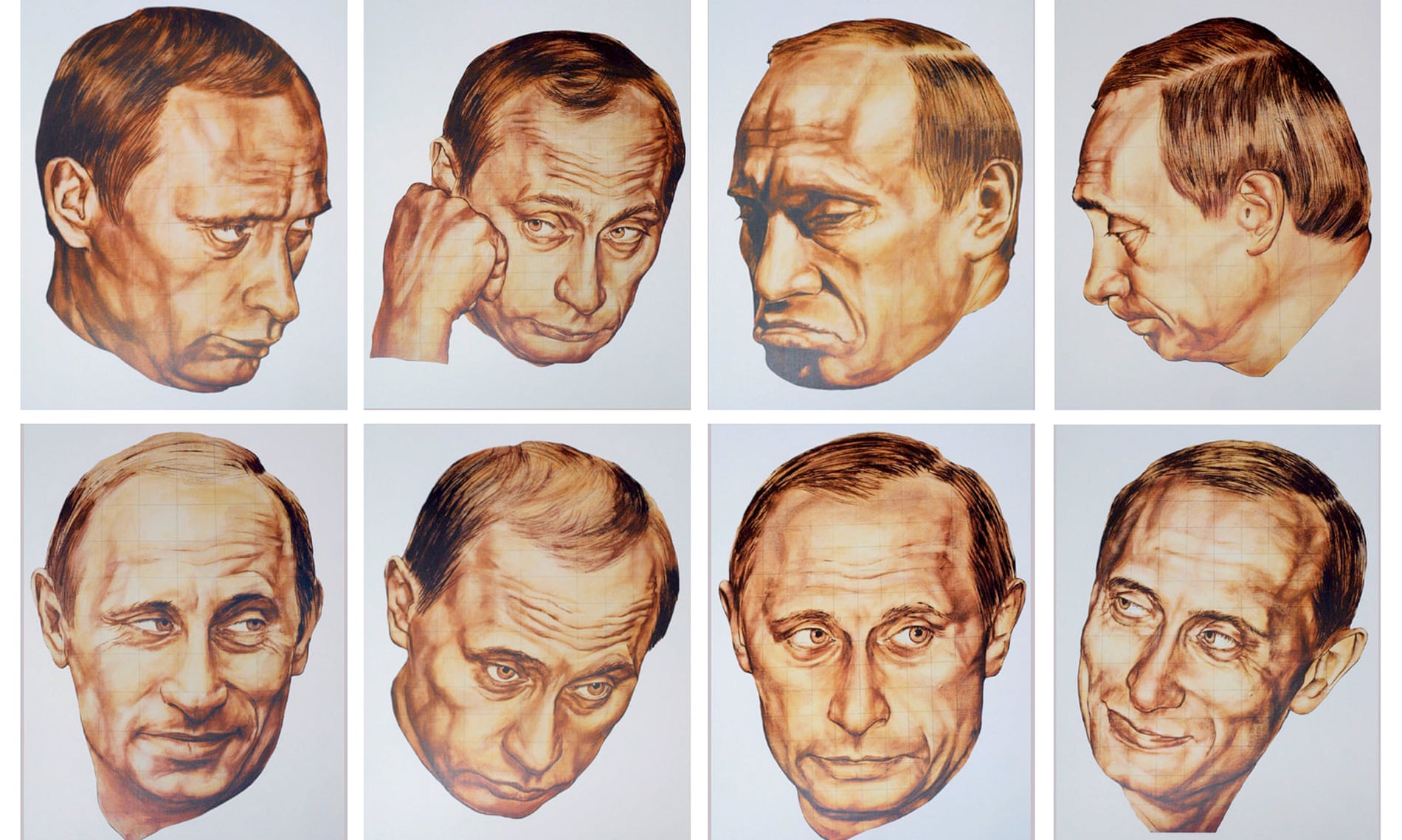

Killer, kleptocrat, Genius, Spy: The Many Myths of Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Putin, you may have noticed, is everywhere. He has soldiers in Ukraine and Syria, troublemakers in the Baltics and Finland, and a hand in elections from the Czech Republic to France to the United States. And he is in the media. Not a day goes by without a big new article on “Putin’s Revenge”, “The Secret Source of Putin’s Evil”, or “10 Reasons Why Vladimir Putin Is a Terrible Human Being”.

Putin’s recent ubiquity has brought great prominence to the practice of Putinology. This enterprise – the production of commentary and analysis about Putin and his motivations, based on necessarily partial, incomplete and sometimes entirely false information – has existed as a distinct intellectual industry for over a decade. It kicked into high gear after the Russian invasion of Crimea in 2014, but in the past few months, as allegations of Russian meddling in the election of President Donald Trump have come to dominate the news, Putinology has outdone itself. At no time in history have more people with less knowledge, and greater outrage, opined on the subject of Russia’s president. You might say that the reports of Trump’s golden showers in a Moscow hotel room have consecrated a golden age – for Putinology.

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian

Don’t Trust Facebook’s Shifting Line on Controversy

Would you tell Facebook you’re happy to see all the bared flesh it can show you? And that the more gratuitous violence it pumps into your News Feed the better?

Obtaining answers to where a person’s ‘line’ on viewing what can be controversial types of content lies is now on Facebook’s product roadmap — explicitly stated by CEO Mark Zuckerberg in a lengthy blog post last week, not-so-humbly entitled ‘Building a global community‘.

Make no mistake, this is a huge shift from the one-size fits all ‘community standards’ Facebook has peddled for years — crashing into controversies of its own when, for example, it disappeared an iconic Vietnam war photograph of a naked child fleeing a napalm attack.

In last week’s wordy essay — in which Zuckerberg generally tries to promote the grandiose notion that Facebook’s future role is to be the glue holding the fabric of global society together, even as he fails to flag the obvious paradox: that technology which helps amplify misinformation and prejudice might not be so great for social cohesion after all — the Facebook CEO sketches out an impending change to community standards that will see the site actively ask users to set a ‘personal tolerance threshold’ for viewing various types of less-than-vanilla content.

Read the rest of this article at: TechCrunch

Donald Trump has inherited the most powerful machine for spying ever devised. How this petty, vengeful man might wield and expand the sprawling American spy apparatus, already vulnerable to abuse, is disturbing enough on its own. But the outlook is even worse considering Trump’s vast preference for private sector expertise and new strategic friendship with Silicon Valley billionaire investor Peter Thiel, whose controversial (and opaque) company Palantir has long sought to sell governments an unmatched power to sift and exploit information of any kind. Thiel represents a perfect nexus of government clout with the kind of corporate swagger Trump loves. The Intercept can now reveal that Palantir has worked for years to boost the global dragnet of the NSA and its international partners, and was in fact co-created with American spies.

Read the rest of this article at: The Intercept

End of a Golden Age

Unprecedented growth marked the era from 1948 to 1973. Economists might study it forever, but it can never be repeated. Why?

The shift came at the end of 1973. The quarter-century before then, starting around 1948, saw the most remarkable period of economic growth in human history. In the Golden Age between the end of the Second World War and 1973, people in what was then known as the ‘industrialised world’ – Western Europe, North America, and Japan – saw their living standards improve year after year. They looked forward to even greater prosperity for their children. Culturally, the first half of the Golden Age was a time of conformity, dominated by hard work to recover from the disaster of the war. The second half of the age was culturally very different, marked by protest and artistic and political experimentation. Behind that fermentation lay the confidence of people raised in a white-hot economy: if their adventures turned out badly, they knew, they could still find a job.

The year 1973 changed everything. High unemployment and a deep recession made experimentation and protest much riskier, effectively putting an end to much of it. A far more conservative age came with the economic changes, shaped by fears of failing and concerns that one’s children might have it worse, not better. Across the industrialised world, politics moved to the Right – a turn that did not avert wage stagnation, the loss of social benefits such as employer-sponsored pensions and health insurance, and the secure, stable employment that had proved instrumental to the rise of a new middle class and which workers had come to take for granted. At the time, an oil crisis took the blame for what seemed to be a sharp but temporary downturn. Only gradually did it become clear that the underlying cause was not costly oil but rather lagging productivity growth – a problem that would defeat a wide variety of government policies put forth to correct it.

Read the rest of this article at: aeon