When OpenAI launched ChatGPT, with zero fanfare, in late November 2022, the San Francisco–based artificial-intelligence company had few expectations. Certainly, nobody inside OpenAI was prepared for a viral mega-hit. The firm has been scrambling to catch up—and capitalize on its success—ever since.

It was viewed in-house as a “research preview,” says Sandhini Agarwal, who works on policy at OpenAI: a tease of a more polished version of a two-year-old technology and, more important, an attempt to iron out some of its flaws by collecting feedback from the public. “We didn’t want to oversell it as a big fundamental advance,” says Liam Fedus, a scientist at OpenAI who worked on ChatGPT.

To get the inside story behind the chatbot—how it was made, how OpenAI has been updating it since release, and how its makers feel about its success—I talked to four people who helped build what has become one of the most popular internet apps ever. In addition to Agarwal and Fedus, I spoke to John Schulman, a cofounder of OpenAI, and Jan Leike, the leader of OpenAI’s alignment team, which works on the problem of making AI do what its users want it to do (and nothing more).

What I came away with was the sense that OpenAI is still bemused by the success of its research preview, but has grabbed the opportunity to push this technology forward, watching how millions of people are using it and trying to fix the worst problems as they come up.

Read the rest of this article at: MIT Technology Review

Typhoons. Scurvy. Shipwreck. Mutiny. Cannibalism. A war over the truth and who gets to write history. All of these elements converge in David Grann’s upcoming book, “The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder.” It tells the extraordinary saga of the officers and crew of the Wager, a British naval warship that wrecked off the Chilean coast of Patagonia, in 1741. The men, marooned on a desolate island, descended into murderous anarchy. Years later, several survivors made it back to England, where, facing a court-martial and desperate to save their own lives, they gave wildly conflicting versions of what had happened. They each attempted to shade a scandalous truth—to erase history. As did the British Empire.

In 2016, Grann, a staff writer at the magazine and the author of “Killers of the Flower Moon” and “The Lost City of Z,” stumbled across an eyewitness account of the voyage by John Byron, who had been a sixteen-year-old midshipman on the Wager when the journey began. (Byron was the grandfather of the poet Lord Byron, who drew, in “Don Juan,” on what he referred to as “my grand-dad’s ‘Narrative.’ ”) Grann set out to reconstruct what really took place, and spent more than half a decade combing through the archival debris: the washed-out logbooks, the moldering correspondence, the partly truthful journals, the surviving records from the court-martial. To better understand what the castaways had endured on the island, which is situated in the Gulf of Sorrows—or, as some prefer to call it, the Gulf of Pain—he travelled there in a small, wood-heated boat.

In this excerpt, of the book’s prologue and first chapter, Grann introduces David Cheap, a burly, tempestuous British naval lieutenant. During the chaotic voyage, he was promoted to captain of the Wager and, at long last, fulfilled his dream of becoming a lord of the sea—that is, until the wreck.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

Beer is about as low-tech as it gets. The oldest surviving beer recipe was unearthed in Mesopotamia, from 1800 B.C., when the Sumerians made a divine drink from fermented barley bread soaked in water with yeast. About 3,000 years later, Benedictine monks in a Bavarian abbey outside of Munich recorded the addition of hops as a bittering agent and preservative. From that day on, those four ingredients — water, fermentable starch (such as barley malt), yeast, and hops — have been the base for just about every beer ever quaffed by humankind.

Those Benedictine brothers could time-warp into a 21st-century brewery and figure out how to whip up a passable batch of ale. Despite the craft beer revolution’s explosion in flavors and additives (everything from doughnuts to cannabis to edible glitter), brewers have painted with the same palette of styles since the 1400s.

But today, as nearly 10,000 U.S. craft breweries jockey for attention and market share, they’re producing more technological innovations in beer-making than the industry has seen in millennia. An innovation race in brewing hardware, ingredients, and recipes aims to help smaller companies brew the same quality beer, batch after batch.

Read the rest of this article at: Experience

Sanctuary

Hurricane Michael crashed through southern Georgia in a fury. Winds whipping at more than 100 miles per hour sheared off rooftops and stripped cotton plants bare. Michael had fed on the tropical water of the Gulf of Mexico, gathering strength. By the time it made landfall, it was one of the most powerful hurricanes in U.S. history.

In its aftermath, Carol Buckley gazed out at the wreckage strewn across her land. It was October 2018. Three years earlier, emotionally broken, she had come to this secluded place just north of the Florida Panhandle in search of a new beginning. Now she feared that she would have to start from scratch once again.

Buckley fired up a Kawasaki Mule and steered the ATV across the rutted fields to get a closer look at the damage. At 64, Buckley had a curtain of straight blond hair, and her eyes were the pale blue of faded denim. Years spent outdoors had etched fine lines into her tanned face. The Mule churned up a spray of reddish mud as she bumped along.

Michael had toppled chunks of the nearly mile-long chain-link fence ringing Buckley’s land. She was relieved to see that the stronger, steel-cable barrier inside the perimeter had held. Felled longleaf pines lay atop portions of it, applying immense pressure, but the cables hadn’t snapped. Installed to corral creatures weighing several tons, the fence stood firm.

Here outside the small town of Attapulgus, near quail-hunting plantations and pecan groves, Buckley had built a refuge for elephants. It was the culmination of a nearly lifelong devotion to the world’s largest land animals. But at the moment, Buckley’s refuge lacked any elephants—and one elephant in particular.

There are many kinds of love stories. This one involves a woman and an elephant, and the bond between them spanning nearly 50 years. It involves devotion and betrayal. It also raises difficult questions about the relationship between humans and animals, about control and freedom, about what it means to own another living thing.

Read the rest of this article at: Atavist

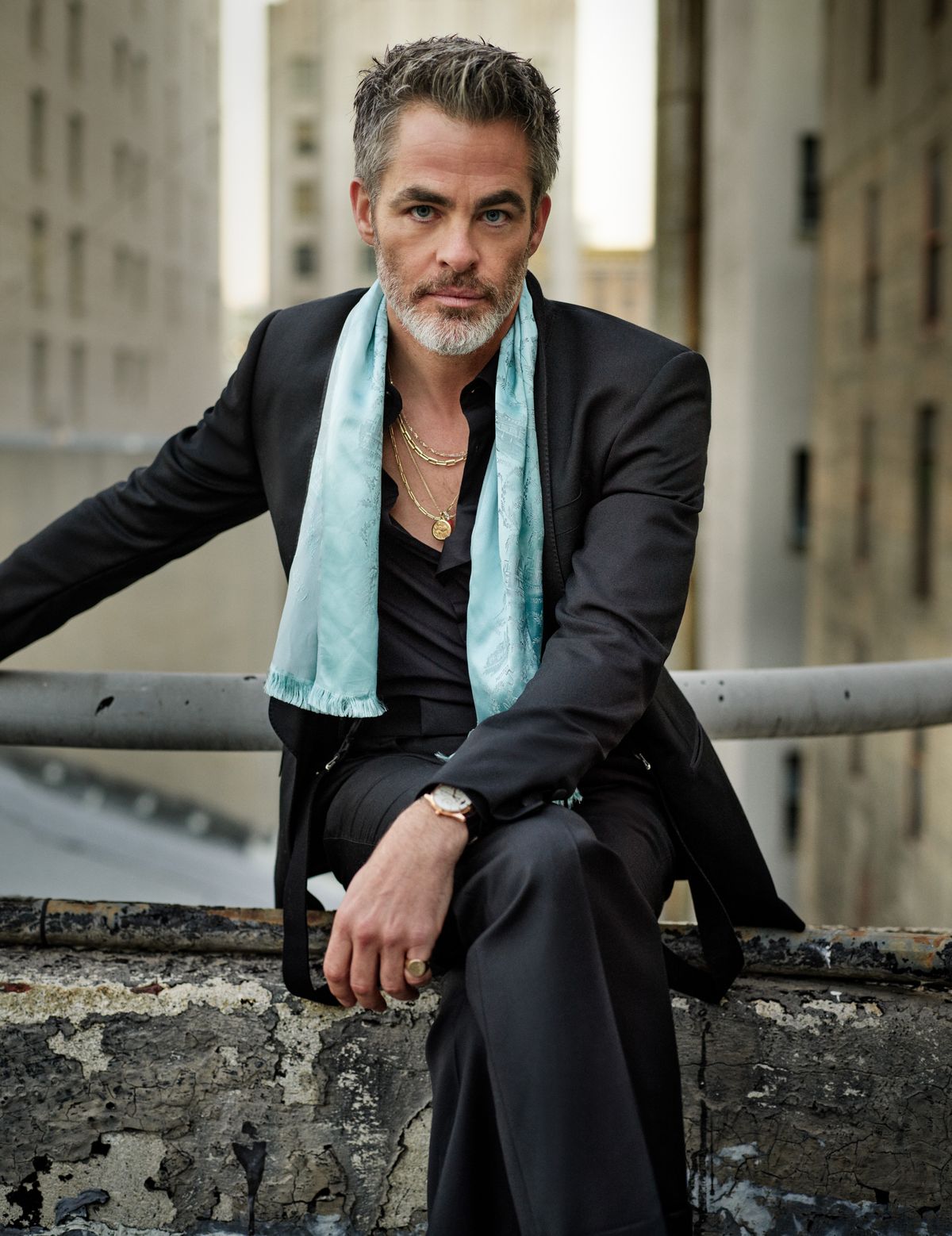

The air in my mouth feels like cotton candy. I reach for the insulated water bottle I’ve been provided. “If you taste something in that,” Pine says, “I put a bit of barley tea in there.” He tried it at a Korean restaurant; now he’s into barley tea. It’s become part of the overall sauna process. Pine enjoys a process. Making an espresso, building a fire. “I love any sort of ritual,” he says. “I can even get into a Catholic Mass because I like the aesthetic. And a sauna is a whole ritual. It’s about gifting yourself a period where there’s nothing to do other than to purify, to release, to cleanse, to start again.”

We’ll sweat and release and cleanse here for twenty minutes, until the heat becomes intolerable, then we’ll hit the unheated outdoor pool—just in and out, a quick car-battery shock to the central nervous system—and finish strong with a dip in the cold plunge, a barrel of what feels like near-freezing water built into the ground. This is how Pine, forty-two, does it every day, except we’re doing it in the morning, and he prefers to do it in the afternoon, sweating out the day’s physical and psychic accumulations. Being out in the world makes him “kind of emotionally and physically tired, so I need some sleep and some sauna time, and reading, and just puttering about in the garden.”

Read the rest of this article at: Esquire