An easy way to measure how much and how swiftly Britain has changed in the age of Brexit is to compare the Britain of 2019 with the image the country projected of itself seven years ago. The last time that pre-Brexit Britain showed itself to the world, the last time it thought hard about its identity, even its own meaning as a country, was on a warm summer’s evening in 2012 when, under the guiding hand of the movie director Danny Boyle, London staged the opening ceremony of that year’s Olympic Games.

Read the rest of this article at: The New York Review of Books

The Tragedy on Howse Peak

Howse Peak is a 10,800-foot twin-tipped spire rising from the Continental Divide between British Columbia and Alberta’s Banff National Park. The area is remote, no cell service or snack bars, although Howse is plainly visible from lonely Icefields Parkway, which bisects Banff just a few miles from the mountain. Only the most serious climbers would consider ascending its east face, a sheer 3,000-foot wall of sedimentary rock marbled with an intricate network of snow and ice. Its most fearsome route, M-16—echoing the name of the machine gun, because of the frozen detritus that routinely showers down it—has only been completed once, 20 years ago, by a three-man team during a perilous five-day effort. One of the men, Steve House, later wrote that the climb entailed “one of the hardest pitches of my life.”

On Monday, April 15, 2019, three of the best alpinists in the world—David Lama, 28, from Innsbruck, Austria; Hansjörg Auer, 35, from Umhausen, Austria; and Jess Roskelley, 36, from Spokane, Washington—skied to Howse and set up a tent in a snow-filled basin, with plans to attempt M-16, or a variation of it, early the next morning. The trio had been in the area for almost a month, staging out of a condo in Canmore. All three were members of the North Face climbing team, a storied group of mountain athletes created in 1992 that includes luminaries like Conrad Anker, Peter Athans, Emily Harrington, Alex Honnold, and Jimmy Chin, among others.

Alpinism is climbing’s most demanding discipline, involving the most objective hazards on the most challenging routes of steep, often fragile snow, ice, and rock. It hardly resembles what most people recognize as mountaineering these days, which is to say the sad circus on Mount Everest or the trade routes on Mount Rainier and Mount Hood. To alpinists, style is everything. Proper progression involves climbing light and fast, with minimal gear and maximum self-sufficiency. First ascents are cherished, though repeating lines of significant difficulty also earns respect. The margin of error is alarmingly thin, and the sport has a long roster of casualties. Roskelley had recently told his younger sister, Jordan, a yoga instructor who works with the Gonzaga men’s basketball team: “If those guys make a mistake, they lose a game. If I make a mistake, I die.”

Read the rest of this article at: Outside

The Year Jim Carrey Arrived

Pam Veasey thought that something was seriously wrong. It was early 1994, and, in the midst of trying to shepherd In Living Color through its tumultuous final stretch, the sketch show’s executive producer got a phone call. “I need to talk to you,” Jim Carrey said somberly.

By then, Carrey had spent four-plus seasons blowing audiences away with his uncanny celebrity impressions (Robin Williams, Jay Leno, even Cher) and zany original characters (Fire Marshall Bill). But the year before, after objecting to Fox’s meddling, ILC creator Keenen Ivory Wayans had left his own show, leaving it in a state of uncertainty.

Veasey was petrified that Carrey was going to walk into her office that day and tell her that he too was quitting. “I’m thinking, ‘What?’” she recalls; after the Wayans incident, she couldn’t take any more bad news. “And I’m like, ‘Jim, just say it.’” At that point, he stood up and pulled a weathered personal check out of his wallet. Veasey recognized it immediately: years before, Carrey had aspirationally written it out to himself for several million dollars; a sort of visualization, done in the hope that putting a physical manifestation of his dream into the world would make it come true. And now it had.

Read the rest of this article at: The Ringer

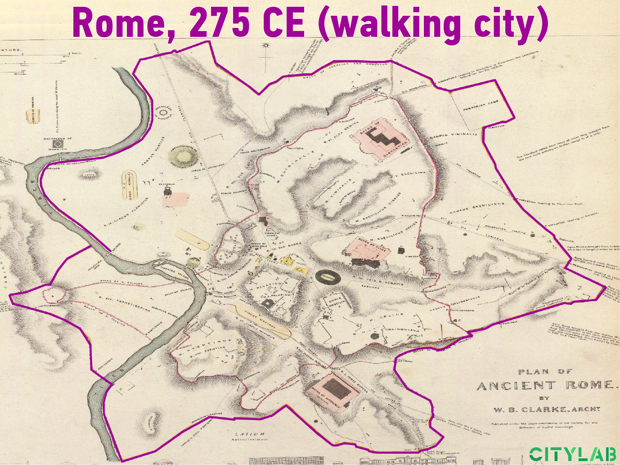

In 1994, Cesare Marchetti, an Italian physicist, described an idea that has come to be known as the Marchetti Constant. In general, he declared, people have always been willing to commute for about a half-hour, one way, from their homes each day.

This principle has profound implications for urban life. The value of land is governed by its accessibility—which is to say, by the reasonable speed of transport to reach it.

Even if there is a vast amount of land available in the country, that land has no value in an urban context, unless transportation makes it quickly accessible to the urban core. And that pattern has repeated itself, again and again, as new mobility modes have appeared. This means that the physical size of cities is a function of the speed of the transportation technologies that are available. And, as speed increases, cities can occupy more land, bringing down the price of land, and therefore of housing, in newly accessed territory.

Modern Atlanta may bear little resemblance to the cities of past millennia, but its current residents share something fundamental with urbanites of the distant past: The average one-way commute time in American metropolitan areas today is about 26 minutes. That figure varies from city to city, and from person to person: Some places have significant numbers of workers who enjoy or endure particularly short or long commutes; some people are willing to travel for much longer than 30 minutes. But the endurance of the Marchetti Constant has profound implications for urban life. It means that the average speed of our transportation technologies does more than anything to shape the physical structure of our cities.

To see how, let’s travel back in time by more than 2,000 years, and move towards the present. (This journey will take less than 30 minutes.)

Read the rest of this article at: Citylab

After an eight-hour shift on her feet, shuffling between a stuffy kitchen and the red vinyl booths of Broad Street Diner, Christina Munce is at a standstill in traffic. Still wearing the red polo shirt and black pants required for work at the diner in South Philadelphia, she’s arguing with her colleague Donna Klum. They carpool most days to spare Klum a two-hour commute on public transportation that involves three transfers.

“It’s not O.K. for people not to tip,” Munce says from the driver’s seat, the Philly skyline passing by. Klum believes that bad karma will catch up with non-tippers, but Munce, a single mother who relies on tips to live, doesn’t care much about their fate. “I have to make sure that my daughter has a roof over her head,” she says. The desire for cash over karma is understandable: Munce’s base pay is $2.83 an hour.

The decade-long economic expansion has been a boon to those at the top of the economic ladder. But it left millions of workers behind, particularly the 4.4 million workers who rely on tips to earn a living, fully two-thirds of them women. Even as wages have crept up–if slowly–in other sectors of the economy, the minimum wage for waitresses and other tipped workers hasn’t budged since 1991. Indeed, there is an entirely separate federal minimum wage for those who live on tips. It varies by state from as low as $2.13 (the federal tipped minimum wage) in 17 states including Texas, Nebraska and Virginia, up to $9.35 in Hawaii. In 36 states, the tipped minimum wage is under $5 an hour. Legally, employers are supposed to make up the difference when tips don’t get servers to the minimum wage, but some restaurants don’t track this closely and the law is rarely enforced.

Waitresses are emblematic of the type of job expected to grow most in the American economy in the next decade–low-wage service work with no guaranteed hours or income. Though high-paying service jobs have been growing quickly in recent months, middle-wage jobs are growing more slowly and could decline sharply in the event of a recession, says Mark Zandi, chief economist with Moody’s Analytics. Those who lose their jobs in a recession usually move down, not up, the pay scale. Jobs like personal-care aide (median annual wage $24,020), food-prep worker ($21,250) and waitstaff ($21,780) are among the fastest-growing occupations in America, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). They have much in common with the burgeoning gig economy, in which people turn to apps in the hope of getting shifts delivering food, driving passengers and cleaning houses.

Read the rest of this article at: Time

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/65124532/02_2.0.jpg)